TL;DR: A long story on how I got started with data, became frustrated with data coaching, and developed a simple tool for self coaching. You can skip this epic tale and print the PDF of the Watkins Glen vMin table.

I’ve been a data coach for a few years, and everyone I’ve coached has made massive improvements. Most of the time data coaching takes just one or two sessions, and on average, I’d say people go about a second faster per mile.

On a short track like Pineview, that’s only one second, but at Watkins Glen, that’s three seconds. Three seconds is like going from a track tire to a slick. Or adding aero. Or buying a lot of horsepower. Any of those things could cost $2000 or more, and so getting three seconds for free is phenomenal. Yes, free.

For a couple years I was the lead data coach for the Niagara Region Porsche Club of America (NRPCA), and we offered free data coaching. While PCA clientelle can certainly afford paying for it, we were trying to lower the bar and get more students interested. Nevertheless, I’d have only one or two students per day.

This became a discouraging waste of time, and so last year I took a hiatus from data coaching. I’ll get back to that again, but in the meantime, I want to share something I invented, which is a vMin table for self-coaching. It looks very simple, but there’s a lot of research and effort that went into it.

It’s a long sorry, hence the TL;DR at the top. I won’t blame anybody for simply clicking the link and moving onto using the tool. But for those that want the backstory, it begins like this:

I never wanted to use data

14-odd years ago I did one or two HPDEs with Hooked on Driving in California, and after seeing a shit-heap of a car on its way to race at Chuckwalla, I convinced my brother and a couple friends to buy a first-gen MR2, cage it, and race it in the 24 Hours of Lemons. For several years, everything I knew about performance driving I learned with the bit between my teeth, going wheel to wheel in an underpowered car, trying to catch faster cars in the corners.

I was good, always setting the fastest times on my team. When we acquired Ben Dawson (Dominating with Dawson, on Garage Heroes in Training), I was able to match his times, but not better them. Then my identical twin brother became a real student of the game, reading Speed Secrets, getting into data, sim racing, instructing… and he left me in the dust.

After being the fastest on the team for a couple years, I was now a few seconds slower per lap. Ian encouraged me to follow in his footsteps, but I countered that I wanted my skills to represent the everyman driver. It could maybe turn into a twin study, where one brother used data, the other didn’t, and look where they ended up years later.

That’s how much I didn’t want to use data; I was willing to let my identical twin trounce me on track, handicap our team’s position in the final standings, pretend to do a bogus twin study, and skill-shame myself with a milquetoast modifier like everyman.

(When reading this article to my wife, she said if people only knew how competitive I am, the fact that I would let my twin brother beat me is incomprehensible. This is the exclamation point on how much I didn’t want to get into data.)

The transition to using data happened sometime after leaving California and starting a new team in New York. Ian flew out a couple times to race my new Miata, and he’d annoyingly show up to some unseen track, and destroy the team’s best times in his first few sighting laps.

It took a while, but the everyman got tired of his everyday beatings, learned how to use data, and then began to coach others through the same process. The track to hell is paved with good intentions.

Data coaching barriers

Data coaching hasn’t taken off for me like I had imagined it would. The reason for that isn’t a hardware problem, since I bring six Aim Solos and assorted brackets with me to all events. Neither was it a financial hardship, because I offered it for free. And nobody ever lost a driving session, since I’d schedule their coaching sessions around that. There were literally no barriers to data coaching, and so the reluctance was puzzling.

Part of the reason data coaching didn’t catch on was due to PCA itself being different from other clubs: we weren’t supposed to talk about lap times, none of the senior instructors were using data or pushing it into the curriculum, much of the clientele were older and skeptical of things new, and in any national organization, change moves at a snail’s pace.

There’s also the “I’m just here to have fun” contingent that comprises most of the people that sign up for a HPDE, and I totally get this group. If I went to a pickup basketball game and some “coach” was on the sidelines saying he could run me through drills between games, I’d walk the other way. The fact is, most of us sign up for track days to have fun with friends, and while the E in HPDE stands for Education, we are really there for the E in Enjoyment.

However, what I’ve found through years of trying to get people to dip their toe into data, the largest barrier to data coaching is this: nobody wants to know they are slow. And they don’t want anyone else to know that either. Pride is the wall that stands between having fun and and going faster.

The thing is, I haven’t met any slow drivers. Everyone has at least one corner where they are fast, and we all have one or two corners where we are slow. You use the former to build on the latter. And that’s what data coaching does – it finds your strengths and creates an individualized strategy to address your weakness. People call it driver mod and it’s a good term, because it’s something you take to every car you drive.

But because pride is more delicate than money is valuable, people will spend thousands on car mods and won’t accept a free driver mod. This was doubly frustrating because NRPCA HPDEs are mostly on weekdays, and so I was burning vacation time to help one or two students per day. So I pondered the incredible value of data coaching, against the struggle of getting people to try it, and I realized this: people will only try data coaching if they can do it in private.

Technological barriers

I wasn’t the only one who figured this out, Garmin did, too. Their Catalyst product combines AI coaching with data privacy in a compact package that doesn’t require a laptop or a professional to review the data.

I read the Garmin Catalyst review by Mark Petronis at AMT Motorsport, and that should have deterred me from buying one, because I’m already an advanced data user. But a virulent case of FOMO swayed me into buying one and experimenting with it for a couple months. I found the following shortcomings.

- The Catalyst doesn’t actually know where you should brake, turn in, accelerate, or track out. It only knows what you’ve already done. so you’ll never know the fastest way around the track, just the least-worst that you’ve done so far.

- If you drive consistently, the Catalyst won’t help; without variation, it returns nothing. You need to make errors in your driving that end up being beneficial mistakes.

- The Catalyst uses only your recent driving. There’s no way to save and then upload best laps from yourself or other drivers to compare with. And so if you live for comparative data (driver mod, tire testing, aero testing, etc), you can’t A/B test jack shit versus shit jack.

- You also can’t download your Catalyst data and then compare it with other people using different devices. This is infuriating, because the Catalyst is gathering GPS data. All I need is a CSV file so I can dump that into Race Studio, but Garmin refuses to play well with others.

- The coaching “opportunities” were mostly good, but occasionally had advice I disagreed with, or missed some obvious wins. For examples of that, see Gregg Vandivert’s article When Garmin Catalyst leaves time on the table.

- The audio hints are fun and come at a good cadence, but the advice has nothing to do with skill, just to drive with more gusto. As useless as the advice was, some of it remains memorable; I can still hear her say “keep pushing,” but it’s mostly her accent, and no longer in the context of driving.

- The Catalyst isn’t plugged into the OBD2 port, so it doesn’t know the most basic information, like whether you had pulled your foot off the gas, braked lightly, or balked a shift. It doesn’t know what gear you’re in, so it can’t whisper “hey there big guy, don’t downshift before the next left, hold 4th gear.”

- There are numerous other quirks or strategic decisions that are baked into the firmware or blocked from export, and I simply don’t agree with a closed system that reeks of rotten Apple products.

In the end, I discovered what the Catalyst is: an excellent delta timer and video camera. [sigh] Perhaps there have been updates that address these issues, and maybe I wasn’t using mine in a way that got the best use out of it. In any case, I sold mine and haven’t looked back. But if Garmin could export the optimal lap video as 10hz GPS data, I’d buy it back at twice the cost.

My requirements must not represent the majority, as I see a lot of Catalysts at the track. However, it appears that most of them are being used as a lap timer and video camera. I rarely see people removing the devices from their cars in between sessions, and so I doubt they are using the coaching opportunities during the day. I guess this is like buying a gym membership and then only using the sauna, but least they are in the right area for self betterment. I understand many people really like their Catalyst, but those people probably never had real data coaching, and accept the shortcomings as a tradeoff for a great UX and data privacy.

On the technological flip side you have Aim products, which sets the gold standard for motorsports data loggers. Unlike the Catalyst, you can plug an Aim SoloDL into your car’s OBD2 port and/or jump into the CAN bus and get brake pressure, throttle position, steering angle, and anything else the car reports on. The amount of data is staggering, and Aim’s decision to display everything by default (including useless data like the device’s internal battery voltage), is complicated and off-putting.

But the true barrier to using Aim products is the software. I’ve worked in software development for 25 years, for companies like Oracle, Salesforce, and Google. I know what good usability looks like, and the amount of effort it takes to take a very powerful tool and make it easy to use.

The Race Studio 3 user interface is a cornucopia of poor decisions, many of which could have been fixed using setup wizards to create custom profiles. Or hire a technical writer like myself to explain how to use three lefts to make a right. But there’s nothing intuitive, streamlined, or adequately documented in Race Studio 3, and so I use Race Studio 2 most of the time, which also isn’t great, but sucks less.

It’s also worth mentioning that unless you put a password on your Solo2, your data isn’t private. When I turn on my laptop in the Watkins Glen garage, I can walk around and pick up everyone’s Solo2 on the wireless network. Because the Solo2 is so damn confusing, most people are using it only as a lap timer, and so they haven’t set a password, and everyone within earshot can access that data.

At this point of the story we come to the realization that technology sucks, and that the best tool for introducing people to data doesn’t exist. If I wanted to get people to dip their toe into the waters of data coaching, I’d need to invent something with the following qualifications: free, private, and devoid of all technology.

[vMin table entered the chat.]

vMin data coaching

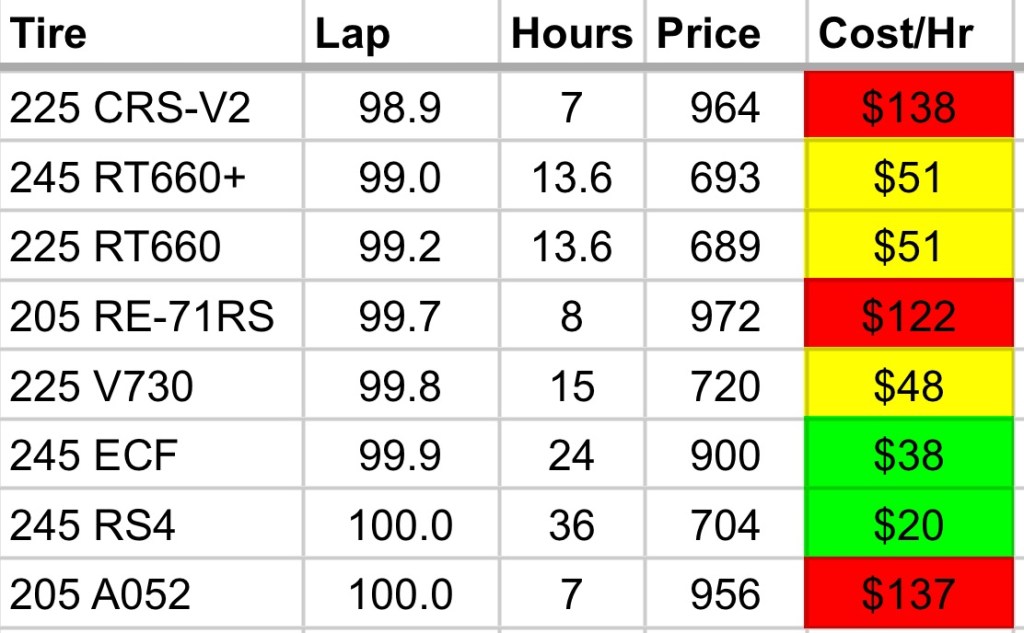

The intro to data coaching tool I came up with is simply a table for minimum corner speed, or as data coaches call it, vMin. Every track has thousands of laps of historical data, and my approach takes advantage of that knowledge, using the best drivers. The primary use of this table is for identifying which corners you need to work on. I’ll show you how to use the table in a minute, but first I want to explain why vMin.

vMin is only a single piece of data, so is it really that important? Well, after seven-and-a-half years of weekly email tips and tricks, Ross Bentley thought so. The final Speed Secrets Weekly #400 could have ended on any subject, but there’s a reason he chose vMin; it’s the thing that separates average drivers from great drivers.

Unlike lap times, which can be bought, setting an ideal vMin is 100% skill. It’s the one variable you can look at that separates the wheat from the chaff. It’s like a unique identifier for expertise, or a genetic marker for driving greatness. Here’s why:

Average drivers throw away entry speed without a thought, and that’s because their thoughts are on two things they learned in the novice group: late braking and early acceleration. When you’re adept at those skills, and combine that with a modern car’s nannies and horsepower, you can pass everyone in your DE group. Advancing to the fastest run group and passing the instructors is simply a matter of more power and better tires.

On the other hand, advanced drivers hoard entry speed like a dragon with its gold; they save it and defend it. Having already mastered late braking and early acceleration, they can instead concentrate 90% of their attention on the last 10% of corner entry. In that very small and compressed zone just before the apex, they make micro adjustments in a delicate dance that maximizes traction, minimizes steering angle, and positions the car for the optimal exit. And they do all of that while retaining the highest minimum corner speed. Herein lies the real art of driving, and if you want just one metric that separates the artistes from the poseurs, you can see it in a single number: vMin.

Another great thing about vMin analysis is that you can still get data in a DE session that’s full of traffic. Unlike looking at lap times, which can be spoiled by a single slow driver, you only need to hit each corner once perfectly, and you’ll have representative vMin data. Of course the more laps you do the more accurate your data is, but the point is, you don’t need to be enraged by backmarkers spoiling a lap, you can still get good data on a crowded day.

Data coaches may add the fact that while vMin is an important metric, where the car is at the point of vMin, and what direction it’s pointing, are actually more important. Yes, I agree wholeheartedly. But if you are able to get that kind of information, then you’re already using data, and this vMin table was not invented nor intended for you! But I will also say that that the where and what direction are already subtly baked into those numbers.

But let’s get back to vMin simply as a number, and not as a position or angle. By raising your vMin speed, you have an advantage until the next corner. For example, at Watkins Glen, let’s say you typically go through Turn 1 at 64 mph. If you can roll another 1 mph through the corner using a different line or technique, that might be worth a full second by the time you reach the bus stop.

Is a higher vMin always better? No. If going through the corner at 66 mph means you’re later to full throttle, then you might be a full second slower by the time you get to the bus stop. So the point isn’t to get the highest vMin in each corner, but the appropriate vMin. If your vMin is at the appropriate speed, and if you’re also at the correct location and angle, and you do this through every corner, this shows up as horizontal line in the vMin table.

Before I explain how to use the vMin table, you should know it’s a coarse measurement, and it’s not perfect. Necessarily so. Later in this article I go into how I created this table, and some decisions I made for ease of use over accuracy. The purpose of the vMin table is to give the everyman a free, private tool they can use to data coach themselves with nothing more than pencil and paper.

Using the vMin table

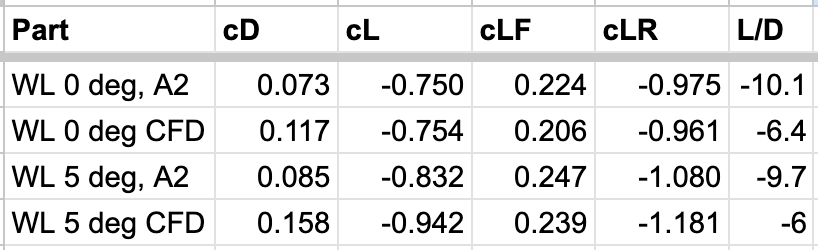

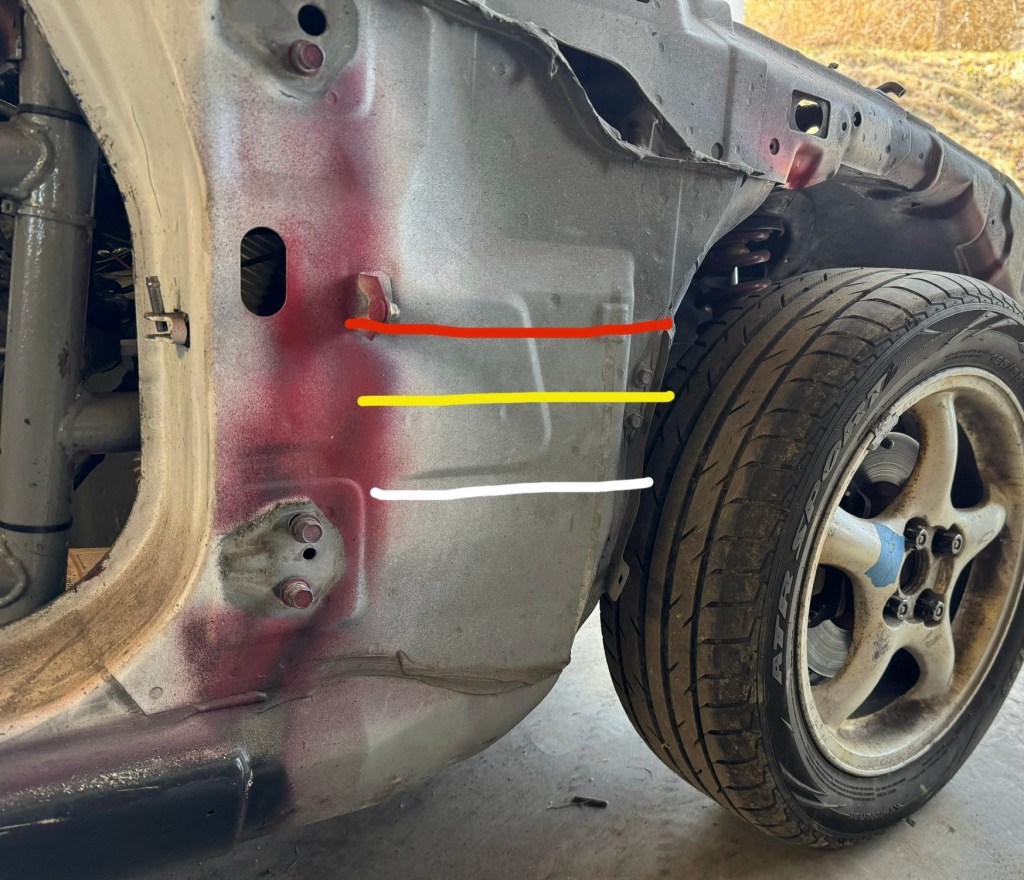

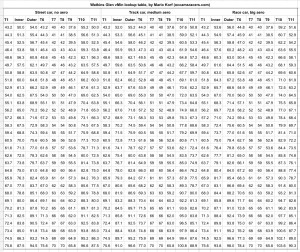

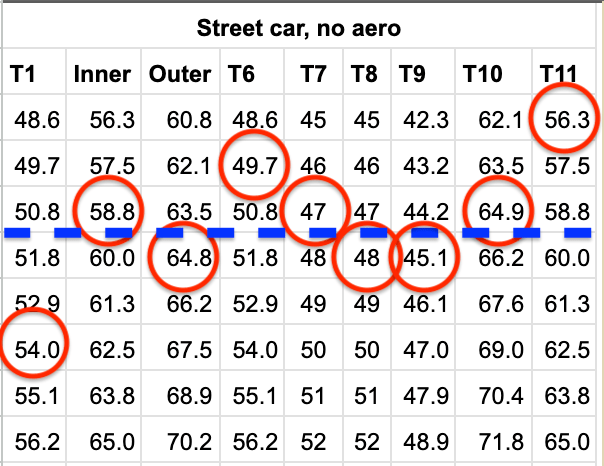

The vMin table (download PDF) shows the ideal minimum corner speeds at Watkins Glen International. It is divided into three columns, based on how much aero your car has. Circle your vMins in each corner, and they should (ideally) form a horizontal line across one or two rows. Speeds that are above that line (slower) are corners where you can increase your vMin. Speeds that are below (faster), indicate that you are either late to full throttle, or can bring several vMins higher.

In the previous image, there’s a horizontal-ish line formed by the inner and outer loop, and turns 7, 8, 9, and 10. But T6 and especially T11 are slower, and are areas for improvement. T1 is faster than other corners, meaning the driver is either late to full throttle, or all corners could be faster.

And that’s basically it. Draw circles around your vMins, look at the ones above and below the line, and try different strategies so that you end up with a horizontal line.

You probably noticed that there are no vMins for Turns 2-3 (the esses). That’s because low-powered cars can’t reach a high enough speed before these corners. If you’re flat footed before, during, and after the corner, it’s really just a straight, isn’t it? For the same reason, if you’re in a slow car, your vMin data for T10 could be off, because you may not reach the T10 vMin on the straight between T9 and T10.

Those caveats aside, one of the great things about vMin analysis is that it doesn’t matter if it’s raining out. All your vMins will come down by the same amount. For that matter, tires don’t matter. If you’re on all-season tires or racing slicks, your vMins should still form a horizontal line.

The vMin table can also be used as a comparative metric with other cars or drivers. If you and a buddy have similar aero (more on this later), you can compare vMins. You may find one of you has a corner you need to work on, and the other has the answer. No data coaches needed, just share driving notes with friends.

Improving your vMins

You’ve circled your vMins on the table, and it’s time to address the outliers. Most of the time you’ll be working on raising your vMins, and so I’ve included various strategies for that below. I can’t take credit for these, it’s things I’ve learned standing on the shoulders of giants. Certainly much comes from Ross Bentley, and his excellent Masterclass online webinars and Speed Secrets books, emails, and other content. I also compare notes with other coaches, and so if you have a method for raising or refining vMin, please contact me and I’ll update the list.

What I’ve found is the best way to raise vMin is deprogramming. We need to challenge our beliefs, break old habits, and even unlearn things we were taught as novices. These are things that we rely on for speed and safety, and they are deeply ingrained. But they are also holding us back. Deprogramming requires a change of focus and a deliberate (sometimes diametrical) change in our actions. By completely changing what you were concentrating on and performing through habit, and intentionally moving that focus and doing something else, you’ll begin to deprogram yourself.

Try to change your focus and actions in the following areas, and see how it changes your vMin.

| Existing focus | Focus on this to raise vMin |

| Beginning of braking point | End of braking point |

| Late braking | Brake earlier/lighter/longer |

| Threshold braking | Release longer, softer |

| Downshifting before the corner | Hold a taller gear |

| Driving a late apex line | Take a late apex as early as you can |

| Always on one pedal | Coast/pause mid-corner |

| Early acceleration | Maintain momentum |

| Setting a fast lap | Learning |

| Driving | Drilling |

Note that different corners will require different strategies, and not all of them will work out. People are different, too. You may find that one strategy works for you, while someone else may have a very difficult time with it. For example, I find that the best way to improve my vMins is doing the no-brakes drill, and that may not be practical for most people who are sharing a crowded track with others.

I’ll explain each of the focus areas, so you understand why they can increase your vMin.

- BoB vs EoB – Most of us have a solid reference for the beginning of braking point (BoB). At Watkins Glen, it’s usually something very obvious, like the 400 board in T1. I’m not suggesting you stop using that, but add a second reference point for the end of braking (EoB) point. It’s deeper than you think, near the apex. By shifting your focus to EoB, you’ll spend less attention on late braking and more on that crucial zone, where the wild things are.

- Brake lighter – For someone who is really good at late braking, it may seem that breaking earlier, lighter, and longer will result in a slower lap time. However, some combination of earlier, lighter, longer will set you up for a higher vMin, and with that, your lap time will come down. You may eventually get back to later, stronger, shorter, but only after you understand the true vMin in that corner, and position your car appropriately.

- Release softer – It’s easy and fun to pass people on the brakes. Drop anchor a fraction of a second later, brake hard in a straight line, and turn in at the last possible moment and you’ve made a great pass. But once the pass is complete, it requires a lot of effort to turn the car sharply at a low speed. If you release the brakes softer (earlier and longer), you can add a little bit of steering into the final part of the braking zone, making the car a wee bit less stable. This will allow you to pivot the car using yaw instead of steering angle, which results in earlier and acceleration and less tire scrub.

- Hold a taller gear -Because the engine has better acceleration at higher revs, most people downshift before the corner. Instead, try holding a taller gear. By not downshifting, you can use all of you concentration on corner entry. By using a taller gear, you can apply full throttle earlier; it’s like a passive traction control system. If there’s just one exercise you try, I hope it’s this one, you may be surprised by the results. If this doesn’t work, then your car may have large gaps in the gearing, and so try downshifting after the corner. This will still free up your concentration on corner entry, while providing more oomph at corner exit. My twin brother has been trying go under 1:02 sim racing a Miata at Brands Hatch Indy, and was stuck there for years. He changed his shifting to after the corner, and can now consistently click off high 1:01 laps.

- Apex earlier – You were taught a late apex line for good reasons, it allows a larger corner radius, earlier acceleration, and it’s safe. Do what you’re doing now, just do it earlier. We call this backing up the corner, and it’s one of the things I look for immediately when data coaching. Whenever I compare two or more drivers, whoever has their vMin further to the left will be the fastest, because they broke earlier, turned the car earlier, and got on the gas earlier. Another reason you should apex earlier is because not all corners require a late apex. But most of us learned the late apex line early in our driving careers, and because it’s so effective, we’ve programmed ourselves to use that strategy in all corners. This is the most common mistake I see as a data coach, but unlearning the school line requires a deliberate change of focus.

- Coast – Whether or not they’ve heard “always be on one pedal,” many people are. They transition immediately from hard on the brakes to hard on the gas. The term is pedal mashing; the definition is slow. You’ve probably seen a friction circle, and understand that if you use 50% of the tire’s traction for braking or acceleration, you only have 50% left for cornering. The result of immediately jumping from the brakes to the gas means the car never experiences 100% of the tire’s grip for cornering. However, if you allow the car to settle in the middle of the corner, then it can use all of the the available traction for lateral grip. We aren’t talking a lot of time spent coasting, it could be just a couple heartbeats between the pedals, but it can pay huge dividends in vMin. If you’re a pedal masher, it may take some effort to delay your transition from brakes to throttle, but try coasting for a full second mid corner, watch your vMins go up, and your lap times come down.

- Conserve momentum – Drive a Miata. No, seriously! Every car is a momentum car, and if you can’t go fast with 90 hp, 900 hp isn’t going to help you. The only way to go fast in a slow car is to conserve momentum, and the best way to learn that is in a Miata. If you can’t borrow or rent one, drive your car two gears taller than normal. It’s probably still faster than a Miata, but you’ll get the point of the exercise.

- Focus on learning – Lap times are an important measurement of self worth, and at some point during a weekend most of us are focused on setting a PB lap. But you only need one, and it’s usually set around 10-11am. So for the afternoon sessions, change your focus to learning, and experiment with things that can raise vMin. You will go slower than normal, but your next morning session will thank you. Also, if you drive a modern car with traction- and stability-control systems, turn off all the nannies, even if it’s raining. Heck, especially if it’s raining. Those things may help you set a fast lap right now, but they are seriously holding you back in the future. In my car, the difference between letting the car’s computer think for me and me thinking for myself is about 1.5 seconds per lap, and that’s on a short 1-mile course.

- Drills – It’s difficult to learn how to play a musical instrument without doing scales or other repetitive exercises. And when you want to learn how to play a song, you need to break it down into multiple pieces and do each piece separately for a while. That’s drilling and it’s an essential part of mastering anything. How much drilling do we do at the track? None. Part of that is because drilling isn’t fun, but it’s also both unsafe and rude to do drills when sharing the track with people who are mostly trying to set PBs. The answer is to use your warm up and cool down laps for drills. But if you want real mastery, you should spend more time drilling than driving, and that requires a mostly vacant track. For this I suggest either becoming a member at a private club like Pineview Run or Circuit Florida, or hitting a less popular track mid-week. I won’t go heavy into which drills you should do, but the no-brakes drill, followed by no shifting, is a good one-two punch that will raise your vMin and drop seconds per lap.

Now that I’ve addressed your low vMins, what about those corners that have a vMin that’s faster than others? These are both rarer and easier to solve. Like in golf, most of us are trying to correct a slice (low vMin), but the odd duck has a hook (high vMin).

If you have one vMin that’s too high, you might be a novice that’s under-driving the whole track. That’s OK, this gives us something to work with! The confidence and skill you’re experiencing in that one faster corner can be applied to every other corner, and all your vMins can come up. Ask you instructor to help you with this, you’re about to drop 5 seconds per lap!

If you’re an intermediate or better driver with one vMin that’s too high, then you’re getting on the gas too late. Review your data in this corner and you’ll see you are either late to full throttle, or rolling off after an initial throttle application, and then reapplying throttle at corner exit. On some corners, this is an appropriate strategy, but Watkins Glen doesn’t have a turn like that.

The reason for your high vMin is likely one of two things. Either you started tracking in a low powered car, in which case your natural default is to conserve momentum, or you simply charged in too fast. Good for you, because too much is easier to fix than not enough! Change your focus to braking and turning earlier (backing up the corner), and get to full throttle before the apex. You may eventually move your acceleration point a bit later, and dial in some maintenance throttle, but to break old habits you need to do something extreme, and changing your inputs such that you can apply full throttle before the apex should do it.

Using the vMin table as a shortcut in data coaching

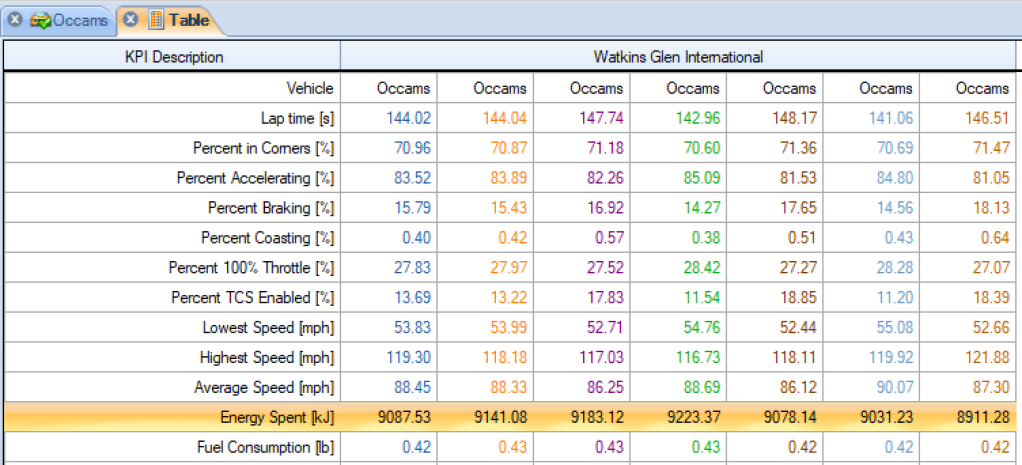

You’ll recall that the purpose of the vMin table was to allow people to keep their data private and coach themselves. What I didn’t expect was that I’d also use this table with every single student I coached at Watkins Glen.

Before I had the vMin table, my normal process was to send a student out for two sessions with the Aim Solo. The first session was mostly to make sure the unit was working and to warm up the driver, but sometimes there are good corners or sectors that are worth saving. The second session is usually the fastest of the day, and I bring them in after that and download the Aim data into Race Studio.

I’d load up their best three or four laps, and look at the the shape of the speed trace. From that I can get just about every input they are doing, and so I don’t need things like steering angle, brake pressure, throttle position, etc. I’ll also look at the time slip on the bottom to look for any large gains due to beneficial mistakes. Next I’ll do a sector time analysis to calculate a realistic theoretical best lap, and expand the histograms to show them how consistent they are. I may then open the friction circle to show the student how they are blending inputs (there’s often a discrepancy in left and right turns), although I could already suss that out myself from looking at the speed trace.

Now that is a pretty long and complicated process, but it’s also very accurate and illuminating. But what I found was that it wasn’t necessary with the average student. Most people have the same things to work on, and it’s easy to grab the low hanging fruit. The largest, lowest, and juiciest fruit is vMin.

These days my process has changed, and after downloading their data into Race Studio, I load up all the laps (not just the fast ones), take a note of the vMins in each corner, and circle them on the vMin table. This allows me to immediately assess the general skill level of the student, and which corners they need to work on.

For example, if I see that T7 and T8 are off by say 2-3 mph, I know the student has some work to do in general. But if those corners are the same, then I can assume a higher level of skill. There are other shortcuts you may discover for yourself, so if you’re a data coach at Watkins Glen, try my vMin table and see if it speeds up your data coaching process as well.

How I created the vMin table

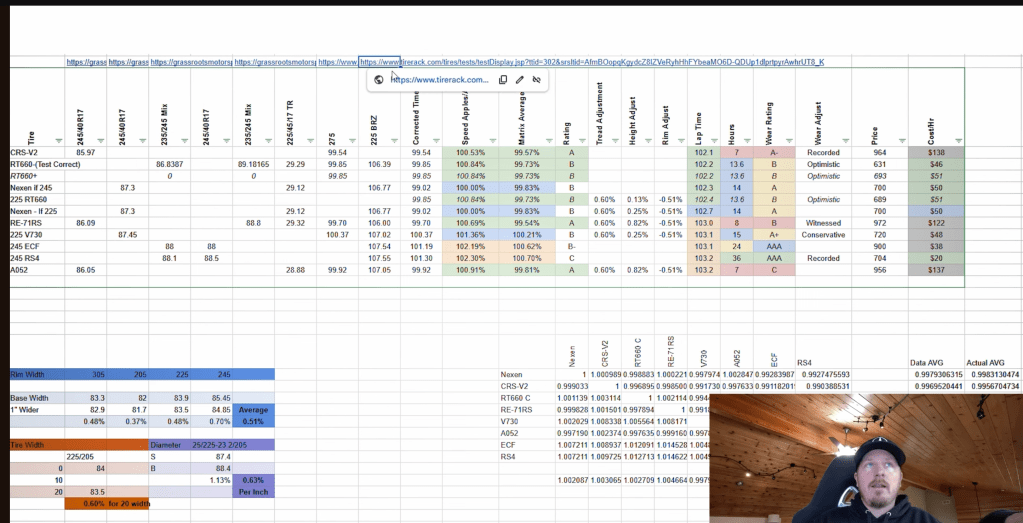

You might be wondering where the data comes from, and how accurate the vMins are. I started by analyzing hundreds of laps at WGI, from rookie drivers to pro racers. I found a lot of 10hz GPS data online, and so it was easy to import a .drk file or convert a CSV from some other system, and then analyze the data in Race Studio.

But when I didn’t find enough pro-level data, I found another way, which was to watch in-car videos on YouTube, and simply jot down the vMins in each corner. It’s definitely a longer and less accurate process, as I needed to watch multiple laps and get the highest vMins in each corner. Data was useless at less than 10 hz, but I found some quality videos online, and it’s worth mentioning the Catalyst videos were excellent. (However, most of the Catalyst users aren’t at a level where their data was super useful.) By combining GPS data with videos I was able to get an expert-level dataset large enough to work with.

After acquiring that mountain of data, I noticed that most advanced drivers go through turns 7 and 8 at the same speed. Drivers of less skill might go through T7 a couple mph faster, or it could be T8, but the best drivers were just about the same speed through both corners.

That got me to thinking of these two corners as a base corner speed, and that every other corner was simply some multiple of the average of T7 and T8. But after some pondering, I realized it wasn’t the average of the corners that mattered, it was the higher of the two. Because the best drivers went through both corners at the same speed, everyone else should be able to as well.

I then looked at my consistent drivers, meaning those who drove T7 and T8 the same-ish speed, and jotted down what their vMin was in every other corner. Then I made that into a percentage of the base corner speed. For example, I found that an expert driver usually goes through T1 at 108% of the base corner speed (the higher of T7 and T8).

Now that I had multipliers on the base speed for every corner on the track, I could make a table for every 1 mph interval of the base corner speed. If you look at the table, you’ll notice turns 7 and 8 are always whole numbers, while every other turn is a decimal value. Now you know why.

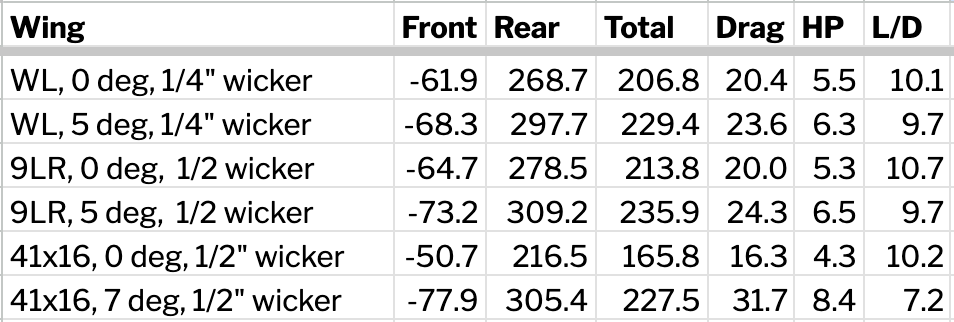

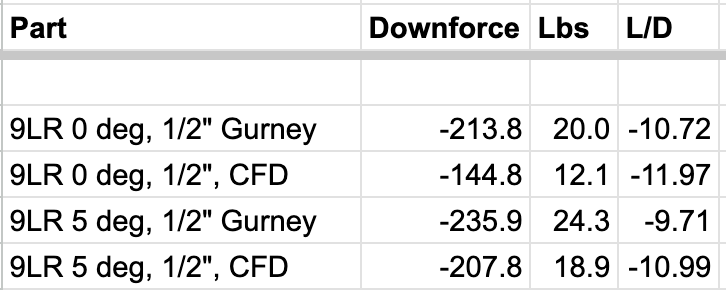

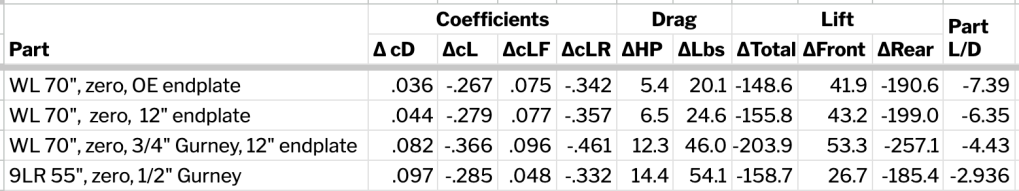

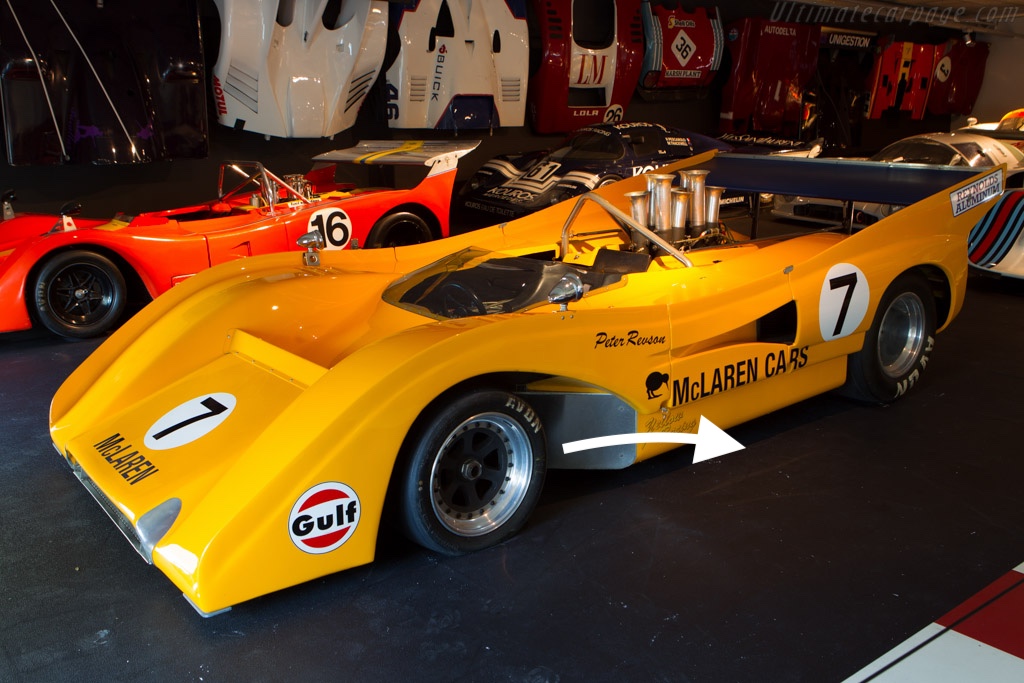

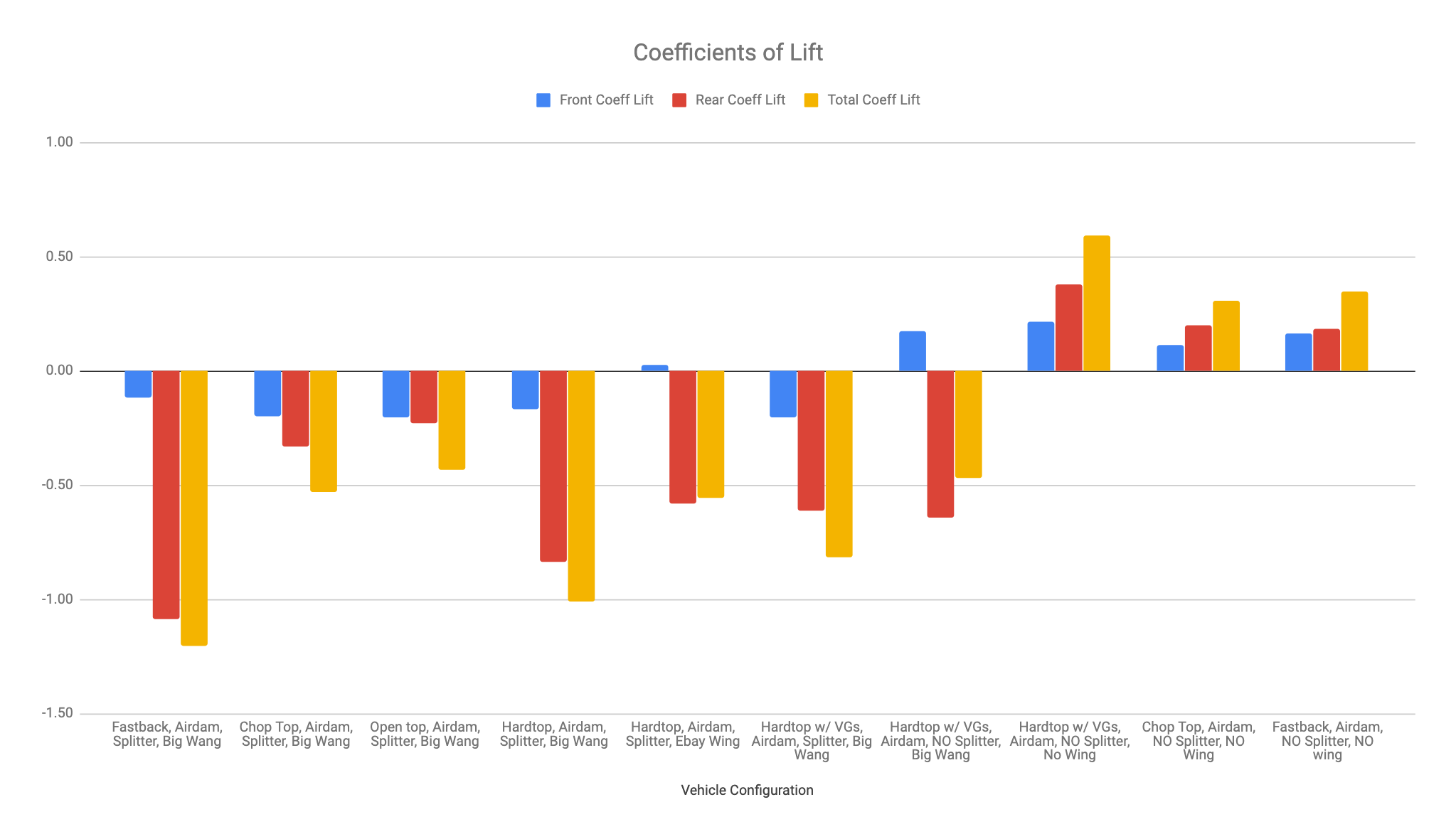

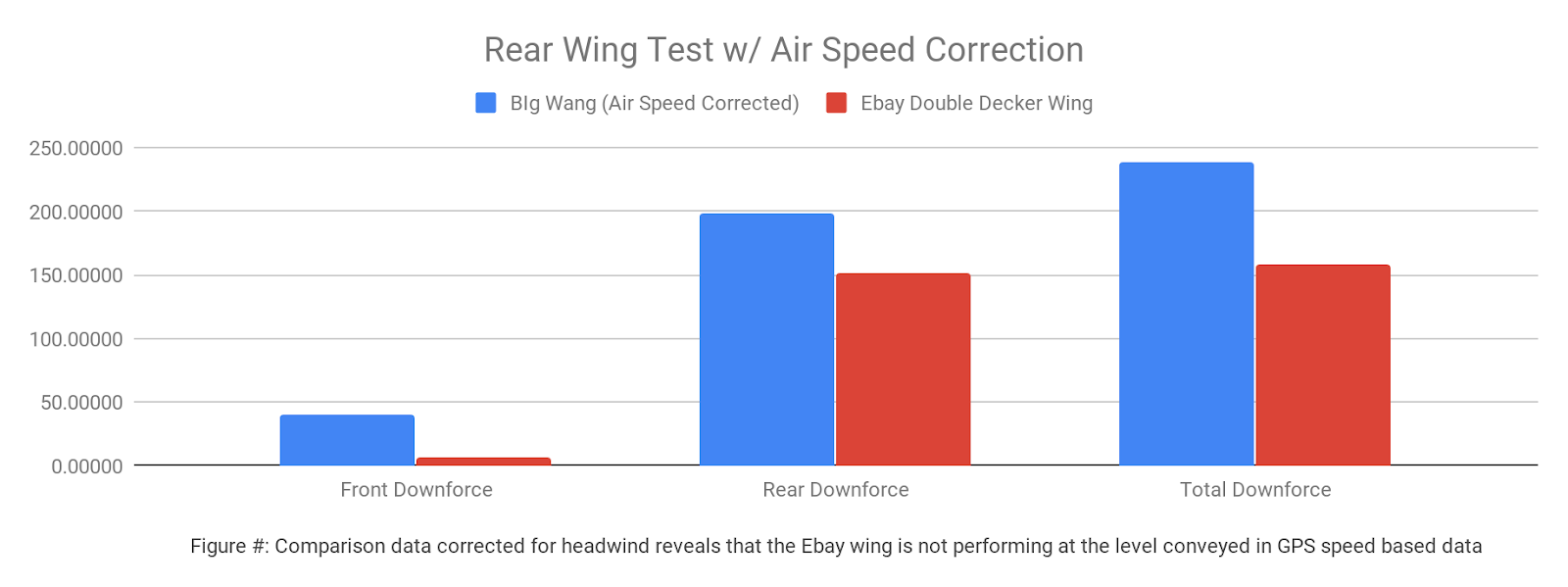

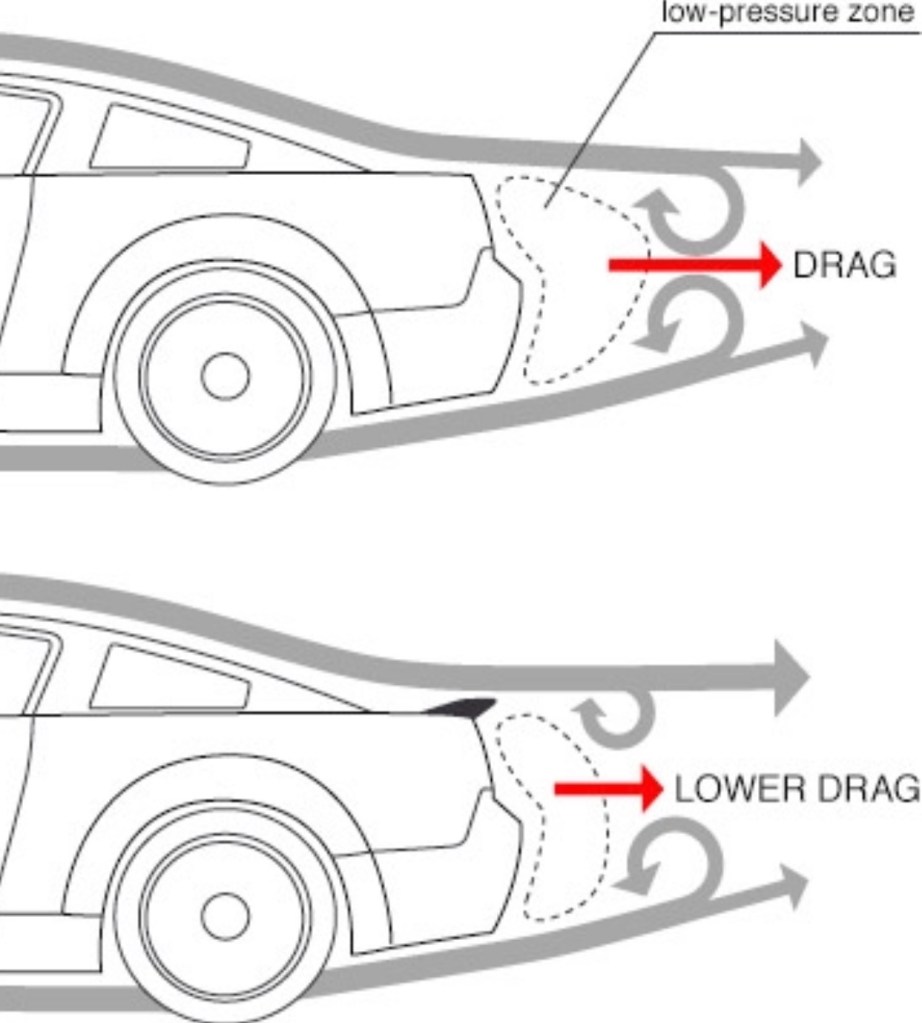

At this point I had a workable vMin table, except for one thing: aero. Cars without aerodynamic downforce lift at speed, which means they lose grip the faster they go. Conversely, cars with aero downforce gain grip the faster they go (well, in relation to cars without downforce). Because WGI has so many fast corners and sees everything from IMSA racers to Spec Miatas, my data was not actually correct, since some cars were lifting off the pavement, and others were pushing into it. For an in depth look at the interplay between tires and aero, see my article on How Downforce Affects Tires, which shows the cornering speed of cars with varying levels of downforce, and their speed through Watkins Glen T10.

To get accurate vMin information, I’d need to know the frontal area and the coefficient of drag and lift from every car in my dataset. This is impossible, especially at the pro level where these secrets are guarded. In addition, pro teams may optimize their mechanical grip for just a couple corners, and make the driver earn their pay in the rest of them. So even if I could get specific aero data on the car, I’m not sure I could use those values for every corner equally.

OK, so instead of 100% accurate data, I figured I could estimate the amount of downforce on every car and log it next to the vMin speeds. After doing that for every car in my dataset, I would then be able to create each car in OptimumLap, run a simulation to see what the difference was in speed and lateral grip, and factor that into the final vMin value for each corner.

That’s a lot of work, but it’s the kind of thing I’m good at. I’ve done a lot of aero research, and combined with my wind tunnel testing, I can make an educated guess on a car’s drag and lift values, and land within a few percent.

After assigning values to every car and running test simulations, I now had an aero factor for each corner. To get accurate vMins, I just had to classify the car’s aero on a scale from 0 (none) to 1 (lots), factor that into my formula, and then I’d know the approximate vMin.

And here I ran into my first usability problem. My initial goal was to create a mathematical formula to say, “if the car has this coefficient of lift, it should go this much faster through the corner.” But this would require the user to know the coefficient of lift on their car, and then apply a mathematical formula to find each vMin value in the table. Nobody is going to do that.

So what I ended up with are three columns to represent aero: none, medium and big. It’s still up to the user to determine which column to use, and for that I’ll provide some quick guidance here, but also you should look at my article on Thinking in Aerodynamic Coefficients.

- No aero – This represents most cars without aero, but also a lot of cars with factory wings, front lips, side skirts, and body kits. None of that OE stuff does much for downforce. Coefficient of lift ranges from +0.25 to -0.1.

- Medium aero – This represents most track cars with wings and splitters or pro-level cars with just airdams and spoilers. Coefficient of lift is all negative (downforce), in the range of -0.3 to -0.8 or so.

- Big aero – This represents professional aero done correctly, and some amateur-level time attack aero. It’s rare to see this level of aero at the track. Anyway, coefficient of lift is -1.0 and better.

As I’m writing this, it occurs to me that you could average the vMins between two adjacent tables, and in that way get five values for aero. That level of accuracy shouldn’t be necessary for most tracks (corner speeds are lower), but that’s kinda neat.

One more thing to note about aero (and it relates to the dataset in general) is that if you compare the three aero columns, the speeds are the same in Turn 1. This isn’t a typo or error on my part. T1 is certainly fast enough for aero to make a difference, but for whatever reason, aero cars and non-aero cars (driven by pro and expert drivers) go through T1 at virtually the same speed, respective to the base cornering speed.

This is why it’s not possible to assemble an accurate vMin table by measuring corner radius, camber, lateral grip, and coefficient of lift, and then running that through a number crunching algorithm. The drivers are the real computers here, and so it’s necessary to see what they are doing in each corner, not what is theoretically (mathematically) possible.

To find out who the best drivers are, it was necessary to quantify driver skill. This required estimating tire grip for each car and factoring that in. Essentially I was asking this: given this tire and aero, how fast should this car be able to go through each turn? This wasn’t terribly difficult because I have a lot of tire data, and I know how to tweak the values in OptimumLap to return realistic values. This got me close, and in some cases I had to slightly correct the values based on what the best drivers were doing.

With all of this information on tires and aero, I could assign every driver a cornering score. What you see in the vMin table is the best of the best. Some of these are pro drivers, but there are quite a few drivers that have pro-level vMins, with only a single corner and/or some consistency they need to work on.

vMins at other tracks?

You might be wondering if I’ve created vMin tables for other tracks, and of course I have. The ADHD part of me loves the dope rush of starting a new project, but then the realization of actually having to finish it sets in. This ends up with me starting another vMin analysis at some new track and not finishing that one either.

But I do intend on releasing more vMin tables in the future. The next tracks are likely Lime Rock, NYST, PittRace, Thompson, and Mosport, all of which I started and then backburnered.

It’s a time consuming process to find all the data, cull that into an expert driver dataset, log all the data in a spreadsheet, calculate a base corner speed, and then figure out the multipliers for each corner. But the endgame where I have to factor in the aero is particularly lengthy and difficult to get right. Now you know why I move on to the next before finishing.

There’s also the fact that not every race track has corners that are useful for vMin analysis. I mentioned previously that T2 and T3 at Watkins Glen don’t have vMins, and the climbing esses at ViR would be similarly problematic in a slower car. Also very long corners, like the Octopus at NJMP Thunderbolt, or the T8-9 complex at Brainerd, just don’t lend themselves well to vMin analysis, since vMin is then very location dependent.

If you have a track that you’d like me to create a vMin table for, contact me and perhaps I can be compelled to start a new one. (I mean, I can always be compelled to start a new one; I really need some motivation to finish one.) But know this: the accuracy of a vMin table depends on having pro- and expert-level driving data from that track to create a dataset. Without that, it’s a non-starter.

Find a data coach

I hope you get something out of the vMin table and try some of the exercises on the reverse side. Most of you will see a significant drop in lap time, but you’ll eventually hit another plateau, because where your car is at vMin, and where the car is pointing, and how long it’s at vMin (thanks Ross) are more important than the actual vMin number. To work on those, you’ll need a data coach.

I suggest hiring a data coach at the track. While there are coaches and services that will analyze your data remotely, having a data coach at the track with you is much more effective. You’ll shorten the feedback loop and get results that day.

If you’re well connected and monied, absolutely go straight to Ross Bentley or Peter Krause. For people coming to Watkins Glen, I suggest the following.

- My data coaching partner Chris White is still with Niagara PCA, and also data coaches for the WGI-based Trackmasters group. So if you make it to Watkins Glen for those events, book time with him, I believe this service is still free. Also, Chris tells me that the vMin table is now being used in the PCA classroom, and so perhaps the worm has turned?

- Gregg Vandivert runs Omega 13 Coaching and is available at several tracks in the northeast. He uses both Aim and Garmin devices at the same time, and combines that with right-seat coaching. I don’t believe you’ll find a better full-service coaching experience. Gregg told me a great story where he got someone six seconds at WGI, and it wasn’t even his student!

- Patroon BMW visits WGI at least once per year and has a great crew of data coaches. They are headquartered in the Albany area, and so you’re more likely to see them at New England tracks like Lime Rock, but look them up if you’re in their area.

- I’m available for private data coaching at Watkins Glen and other tracks in the Northeast, but I prefer to do this at Pineview Run. I have a lot of comparative data there, the track is usually pretty empty, and the lodge is air-conditioned with big tables where we can sit and review data. Pineview is a highly technical track, and so it can be even more useful if you’ve never been there before, as you can test your assumptions on driving strategy versus a mountain of data from other drivers. I have a sliding scaled based on dates (was I planning on being there already) and whether or not you own a Porsche.

- If you’d like to get drill-based instruction and data coaching from me and Ross Bentley at Pineview, sign up for the Ross Bentley Driver Development Program. The 2-day class doesn’t include data, but the 3-day class does, and is offered only on July 25-27. The cost is $4000, but the driver mod will be worth it, many times over.