I plan on doing a few tests at Watkins Glen International this year, and this is the first of (I hope) several reports. WGI is 25 miles from my house, and I have a lot of opportunities for free track time with groups I instruct for (Chin, HoD, MT, NASA, PCA, SCDA). The Glen is convenient for testing, and the corner speeds are high, making it a good place to test aerodynamic downforce. But the straights are also quite long, and so drag matters a lot here.

However, as a testing venue, WGI is only so-so because it’s a popular track, and so there might be 40+ cars in your run group. It’s not just the traffic that’s the problem, but highly variable weather, and virtually no runoff. So it’s not uncommon to lose a session due to rain, fog, or because someone hits a wall. For this reason, I may need to use sector times and predicted laps in order to get good data.

But on April 13th we had decent weather and lots of space on track with Mass Tuning, and so I was able to test different things and get clean laps. But because I made aero changes each session, and was also playing taxi (guest rides), I wasn’t able to string together many hot laps, and so there are only three decent laps from each aero configuration.

Another reason for the lack of hot laps is it takes a full three laps to get my tires up to temperature. I start them at 27 front and 30 rear, and at the end of the session they are properly at 37 F and 36 R. But I lose a lot of time early in the session, braking and accelerating hard to get the temps up, while keeping corner speeds low. If I’m impatient and corner hard at less than 32 psi, the tires roll over and I cord the outer edge. I learned this the hard way last year, getting only about 1/3 of the life out of my tires.

In the future, I may start the tires at 30 psi, which should put the tires out of the danger zone after one lap. This would result in the front tires being 40-42 psi for most of the session, and while this won’t return the best lap times, I should be able to normalize the data better.

The long warm-up times are probably the result of not enough negative camber. In fact I never hear the tires working hard, they just make a low-frequency moaning sound, not the screeching howl I get out of my Miata on the same tires. The Veloster sits on lowering springs and has one set of camber bolts, and this maxes out the camber at -1.8 degrees. With offset bushings (or slotting) it’s possible to get -2.5 degrees, but any more than that and I risk blowing the OE struts. This is still a street car, and I’m not going to ruin it by turning it into a track car with coilovers, stiff sway bars, and solid bushings. Well, not yet anyway.

OE N wing 2:17.4

In the wind tunnel, the OE wing (or it could equally be called a spoiler) made 30.8 lbs of downforce at 100 mph. This cancelled out the rear lift on the base model hatchback, giving the car a slightly negative coefficient of lift. This is very rare in a street car. In my article Thinking in Aerodynamic Coefficients, I show that most cars have positive lift of around Cl 0.1-0.2. Cars that have zero lift or even some downforce are rare, and usually an exotic sportscar. But the Veloster N is one of those unicorns that has downforce straight from the factory.

The OE wing does a good job of stabilizing the rear of the car, and I felt none of the rear instability issues I felt when testing the car with the base model roof extension (meaning no wing). That was a test I ran at NYST, and the rear lift made the car twitchy under braking going into T1 and T5. But at WGI where I was 30 mph faster, the N wing felt stable under braking, and so the OE wing is definitely an improvement on the base model’s featureless roof extension.

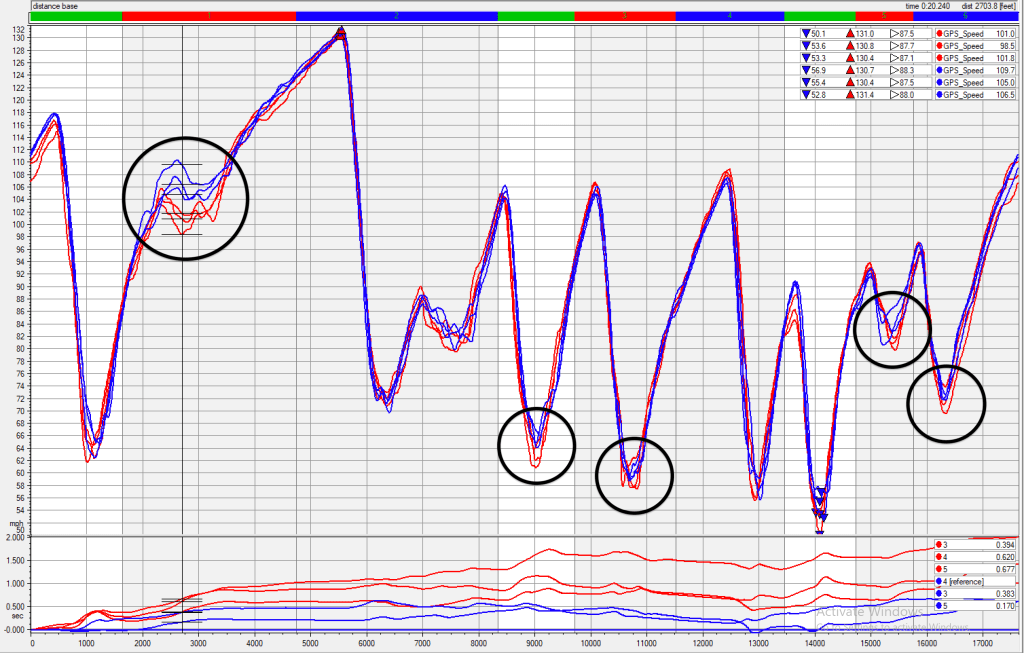

The N wing also had the least drag, and posted the fastest top speed of 132 mph on the back straight. But the OEM wing also had the least downforce, and you can see this on the speed trace below, where I compare the OEM wing (red) to the same wing with a Gurney flap (blue). Note the difference in speed through the esses, it’s huge. But also note the vMins in each corner that I’ve circled. Not only are the vMins higher, they are shifted to the left, indicating that I’m backing up the corner better when the car has more rear downforce.

Wicker kicker 2:16.4

I put a 1” tall Gurney flap (wicker) on the trailing edge of the N wing, and in the wind tunnel this made 114.7 lbs of rear downforce and 8.9 lbs of front downforce. The fact that this made front downforce means the wing is behaving more like a spoiler than a wing, and the combined 123.6 lbs of downforce is a lot more than I would have thought from adding a simple Gurney flap. When I add a Gurney flap to a wing I usually get 150-170% more downforce, not over 400% more! With an increase in downforce, there’s more drag, and 8.3 hp is lost at 100 mph.

But the extra grip through the esses is worth it, and by the time I get on the brakes for the bus stop, the max speeds are identical with or without the wicker. Around the rest of the lap, the modified OE wing has more grip, and the lap times are 1.1 seconds faster, lap after lap.

I uploaded a video of three consecutive laps, and I apologize in advance for the shitty audio. I use an original SmartyCam with an internal mic, and I can’t figure out how to make it less terrible. Anyway, I do a brace of identical 2:17.031 laps (down to the thousandth of a second!), on either side of a 2:16.415.

S1223 54×11 wing 2:16.8

In the wind tunnel, my DIY Selig S1223 wing made 179.5 lbs of rear downforce at 100 mph, and 31.6 lbs of front lift. Wings are located higher and further rearward than spoilers, and so it’s normal for wings to lift the front end through leverage. As a practical matter, this is why people typically use a splitter and a wing together, but a spoiler can often be combined with a simple airdam, or just used on its own.

The wing’s total downforce of 147.9 lbs, divided by 45.3 lbs of drag force, returns a 3.27:1 L/D ratio, which is about the same as the OE wing, but not as good as with the Gurney flap. The drag amounts to 12 hp at 100 mph, and on the back straight of Watkins Glen, the wing is 2 mph slower than the other options.

One of the reasons the wing isn’t very efficient is because it has a span of only 54”. This is problematic for two reasons: first, wing-tip vortices have a detrimental effect on the wing’s overall performance, and so the greater the aspect ratio, the better the wing performs; second, most of the wing is in the silhouette of the hatchback roofline, and so very little of the wing is in clean air.

The reason the wing is 54” is because I wanted a cheap way to test a dual element wing, and bought a $35 extruded wing as the upper wing. The dual wing worked well at Pineview Run and NYST, setting the fastest laps (.8 seconds and 1.0 seconds faster than the single wing, respectively). But after seeing the initial results from the single wing at Watkins Glen, I didn’t even bother attaching the upper wing, as I’m sure the dual wing would have been the slowest.

Under most racing rules, wings are allowed to be body width, which in the case of the Veloster N would be 71.7”. I tested a 70” Wing Logic wing in the wind tunnel, and it made the same amount of total downforce as my 54” DIY wing, but with 44% of the drag. The resulting 7.4:1 L/D ratio shows how important it is to get the wing tips as far apart from each other as possible, into clean air, and away from the hatchback roofline. I may test this on track in the future.

Conclusions

Based on testing the single wing at Pineview Run (.7 seconds faster) and NYST (1.5 seconds), I felt for sure the S1223 single element wing was going to be worth 3 seconds at WGI. The fact that it was only worth about 1 second has me tail spinning into the D-K pit of despair. Let me think about why that may be….

One reason for the lack of performance may be the aero balance. As mentioned, the wing adds rear downforce with a lot of leverage, and so it was the only one that lifted the front. The result is the car may have too much rear aero bias, and not enough grip for turning in. Perhaps when I put a splitter on the car, I’ll see better results.

But note also that the aero balance was even worse at NYST and Pineview. The fastest rear aero on those tracks was the double wing, which I didn’t measure in the wind tunnel, but certainly has the most downforce and drag.

Another reason the wing underperformed could be the driver underperformed. I don’t believe I was cornering hard enough, and just barely edging into the performance envelope where aero is adding to what the tires alone can give. With more laps and coaching, we may see the driver perform better, and with that, the results may change.

Of course drag is a factor at Watkins Glen, and the 54” wing had the most drag. If I swapped to a 70” Wing Logic wing, I’d gain the equivalent of 6.7 hp (at 100 mph).

But as it sits now for both car and driver, the easiest and cheapest way to go faster in a Veloster N is to put a 1” Gurney flap on the OE wing. The performance of this modification was one of the biggest surprises in the wind tunnel, and it’s nice to see that reflected in real life, as well.

Three hot laps from each configuration went like this:

| Config | Best lap | Average | Predicted |

| OEM wing | 2:17.434 | 2:17.91 | 2:16.841 |

| OE + wicker | 2:16.415 | 2:16.83 | 2:15.783 |

| 54″ wing | 2:16.795 | 2:17.02 | 2:16.284 |

While I have some work to do to get faster, I’m a consistent driver. Watkins Glen is a long 3.38 miles, but my lap times are usually within a couple-three tenths of the previous lap. That’s around a 0.3% difference, and probably similar to the noise you’d see in other variables that change throughout the day, such as air and track temperature, wind speed and direction, etc.

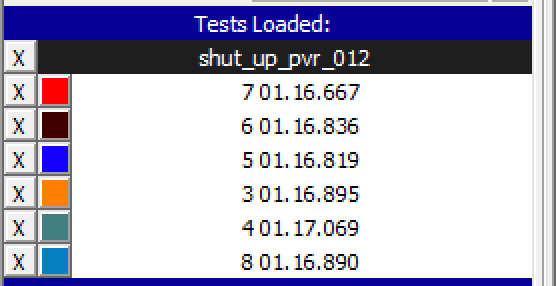

<brag>On a track that I have more laps on, like Pineview Run, I’m a metronome. Here’s six laps in a row with 0.372 seconds between all of them. If you throw out the fastest and slowest, I do four laps separated by 0.076 seconds.</brag>

I mention this not just so that I can thump my chest, but to throw some validity on track testing aero components. There are a lot of variables that change throughout the day, or even within a single track session. As those tolerances stack up, lap times can vary a lot. However, my driving is probably less of a factor than you might think, and I just want to point that out so I can deflect some of the “you’re driving like shit” comments. (Which are true, but at least I’m consistently driving like shit.)

Future tests

For Watkins Glen to be useful as an aero testing venue, I’ll need to fix my attitude, and turn my frown upside down. I’ve never gotten along well with this track, and I have to get to the point where I enjoy driving here. With some help from Gregg Vandivert (Omega 13 Coaching) and many more visits to the track, perhaps I can flip this script.

[sigh emoji] I hesitate to list the tests I want to do in the future, because the best laid plans of mice and men usually amount to the same dung heap of disappointment. But if things go as planned, I’ll test the following:

- Driver mod – I’m curious to see how much time I can lose from professional coaching alone. In order to A/B test myself, I’ll need to use the same baseline setup and pray for days with similar weather.

- Splitter – I didn’t use a splitter in any of these tests because I was matching the same setup I already tested at Pineview and NYST. But now that I’ve done those tests, I can put a splitter back on my car and see how this compares to the wind tunnel, and how getting more front aero load helps the overall balance. Naturally I’ll need to test the splitter at various heights and angles of attack, and so this could be a whole day of testing on its own.

- Canards – I tested canards in the wind tunnel on two different occasions, and now it’s time to take the best results and see how they do in the real world.

- OE wing modifications – The 1” wicker worked great on the OE wing, but I’ve only tried the one size. Next I should try 1/2” and 1.5” tall, and see what happens. Also, I believe that getting the OE wing a little higher may increase performance, and with that, I could also add some angle of attack. This should be as simple as installing a few shims beneath the wing.

- Ducktail spoiler – I tested a DIY spoiler at Pineview and the results were similar to the single wing. But WGI has already proven to be quite different than other tracks, and so I should test this one.

- Bigger wings – The wind tunnel already showed me how important wing span is, and so a 71.7” wing will be a lot more efficient. I’m building a big wing now, and shall test this for sure.

- Active aero – I wrote an article on active aero, in which I did racing simulations at Watkins Glen. Now it’s time to put my money where my mouth is and do the same experiments in real life. The easiest active aero to fabricate would be a DRS spoiler, so I may start with that rather than jumping straight to a dual wing.

- Diffuser – I tested a diffuser in the wind tunnel and it was pretty lousy, losing about as much front downforce as it made in the rear. But the A2 wind tunnel doesn’t have rollers for the wheels and so the effect of the underbody can’t be 100% trusted. So I should probably test the diffuser IRL and shoot myself up with another dose of disappointment.

vMins and driver performance

If you saw my previous post on vMins, you may wonder how well I performed on the vMin table. I put the OE wing on the Street table, and the modified wings on the Track side.

The red circles indicate my vMins with the OE wing, and you can see that I’m OK, but not great. My T7 may be a bit high, or more likely, all of my vMins can come closer to that level. However, when I add rear aero, I park it in the bus stop! I’m probably using the same braking marker, and then just over-slowing the car with the extra downforce and drag. I expected my vMins to be a lot worse than this, so I’m pleasantly surprised that I’m not driving like shit. And at least I know what to work on next time.

Gran Turismo nerds

I prepared for my Watkins Glen weekend by doing some laps in Gran Turismo 7. GT7 doesn’t have a Hyundai Veloster N in the game, so I’ve been using a Scirocco R. Now that I have data to refer to, I can modify the car to be as close as possible to the real world.

In the game I set the car weight to 3000 lbs and the horsepower to 244 (buy the lightweight modifier and add ballast weight and a power restrictor). This approximates the dry weight of my car (I have lighter wheels and the rear seats removed) and what my car puts out on the dyno (my engine is bone stock, not even a cold air intake). More importantly, this also gives me a realistic speed of 132 mph on the back straight. (I’m sure you could use a heavier car with more power, but this is just what I landed on.)

I also fitted the non-adjustable Sport suspension because I have lowering springs, and added the Sport brake pads (which do nothing in the game, but I’m trying to match the car IRL). I added a rear wing so that I can adjust the rear downforce from low (OE N spoiler) to high (single wing). GT7 doesn’t simulate aero accurately anyway, but I added no other downforce because I’m not using any. I use Comfort Soft tires, which puts the corner speeds in the right window for Hankook RS4s with painfully not enough negative camber.

If you have GT7, make a Scirocco R like this and play along. The PP value should be 492 with the wing maxed out. You can drop a comment here or contact me if you want to compare notes.

With the Scirocco R set up like this, I can click off low 2:14 laps regularly, and get the occasional 2:13 at WGI. That’s 3 seconds faster than I’m doing in the real world, which seems about right seeing as I can drive much harder in the game than IRL. As I get better in the real world, I expect the lap times to get closer to GT7. We shall see.

If you made it this far, thanks! If you’d like to support more content like this, hit the Buy Me a Coffee link. If you’d like the Veloster Wind Tunnel Report, it’s just $25 and goes through a ton of stuff you can do to make your car faster.