I’ve had my Veloster N for a year and a half, and with two track seasons finished, it’s time for a retrospective. I’m not going to get into daily driver details, just going to review the important things; race track things.

Wheels

Most people downsize the OEM wheels from 19” to 18” because aftermarket wheels are much lighter, and 18” tires are usually about 20% cheaper. The big challenge is fitting wider wheels and tires; unless you cut the fenders and install flares, the Veloster N can’t fit wide tires. When you compare the wheel and tire sizes to other cars, the Elantra N can easily fit 245 on 9”‘ wheels, while a Civic Type R can fit a 265 on 10”. It’s just not fair.

Ergo, VN track drivers typically fit a 235 tire on 18×8.5 +45. My buddy Chris was able to fit a 245 RT660 on a 8.5 +50, but he was at stock ride height. I tried the same tire on a 8.5 + 45 with 1” lowering springs, and it rubbed front and back.

I have three sets of wheels:

- OEM 19×8+55 – Theres nothing to like about the stock wheel, it’s narrow and weighs over 29 lbs. When I wore out the OE Pirelli PZ4 tires, I put $65 Linglong Crosswind tires on these wheels, which is better rubber than they deserve.

- Konig Countergram 18×8.5 +43 – I bought these because I like the black center and polished aluminum lip. They were about $300 at Fitment Industries and weigh 19 lbs. I have only used these for Kumho V730s, and they fit fine.

- Motegi MR140 18×8.5 +45 – These are a bargain at $173 from Phil’s Tire. The only downside is the mounting holes are super narrow, and even 17mm lug nuts won’t fit, so you need to use spline (tuner) nuts, which I fucking hate. Anyway, the wheels are cheap and at 19.1 lbs, quite light. I used these for the 18” PZ4, Blu Trac Race, Pilot SS, and RT660.

I’ve read somewhere that reducing rotating weight is 3x more important than weight elsewhere on the car. So taking 10 lbs off each wheel is a huge benefit for acceleration and braking. Being unsprung weight, this also helps handling.

Tires

I put camber bolts in my Veloster N, and it maxes out at -1.8 degrees of camber. I understand that the DCTs can get more camber than the 6M versions, but I don’t exactly understand why. In any case, this doesn’t allow my car to get the most out of a proper track tire, and so the difference between an all-season and a super 200 is less what it should be. Or another way of putting that is that my car goes well on shitty tires.

At this point I’ve track tested eight different tires, from cheap all-seasons, to max performance summer tires, a few 200s, and a premium 100 treadwear. All of these were properly abused on the same race track, and I dutifully collected data for comparative analysis.

I’ll list them in the order I drove them (including two tires on a friends Veloster N), and sum it up with a report card.

- Pirelli PZero PZ4 – I’ve had these in the OE 235/35-19 on 8” wide wheels, and 235/40-18 on 8.5”. I felt they were decent rain tires, but otherwise just average. You need to keep the pressures high to keep them from rolling over, and rotate them frequently, as they deteriorate quickly on a dry track.

- Falken RT660 – I drove these in a wider 245/40-18 on my buddy Chris’s VN, and came away solidly impressed. On an otherwise stock VN I was only .25 seconds off Pineview’s all-time FWD record. Chris’s car doesn’t have a lot of camber, but he had the tires heat cycled before delivery, and thus experienced none of the center delamination or tread splice issues that others have reported.

- Maxxis VR1 R2 – The Hankook RS4s used to be my favorite dual duty tire, but it’s not always available, and rarely on sale. Maxxis VR1s are pretty close in performance, and a great second choice. I used this tire on Chris’s VN and went a little slower than I did on the RT660. On the other hand, Chris didn’t like the feel of the Falken’s and went faster on Maxxis. This goes to show you that it’s not always the outright grip that matters, and you might turn a faster lap on a tire with less grip. Feel, feedback, and confidence are important.

- Linglong Crosswind UHP All Season – I bought these because I needed something (anything) to put on my 19” OE wheels after the PZ4 wore out. At $65 on sale, I didn’t expect much more than round and black, but I took them to the track just the same. The sidewalls were mush and they howled like a chorus of tone-deaf banshees, but the performance wasn’t terrible. Three different drivers flogged them all day long, and the budget 400 TW tires earned some respect.

- Kumho V730 – This is a good dry track tire, but worthless in the wet. It has a NT01 feel, with great feedback and grip that’s good down to the cords. While searching for more grip, I aired them down too low and corded the outside shoulder with half the tread remaining. I can’t start these at less than 32 cold, which means they’ll come up to 41 psi hot, and so I have to pit once and air them down, which is a PITA. They are cheaper than most 200s, and if the car could get more camber, I’d use nothing else.

- Armstrong Blu-Trac Race – Armstrong left the e off of Blu and the k of off Trac and the grip off a 200 TW tire. And yet this was the most fun tire I’ve tried so far. They break away very early, but are super easy to control when sliding. You can get them with a money-back guarantee, and they go on sale a few times per year. This tire puts the E in HPDE.

- Goodyear Eagle Supercar 3R – I admit that I often order food looking at the right side of the menu, and so it’s not surprising that I buy tires by price. But this summer I decided to spoil myself for once and get a premium tire and set some PB laps. The grip of the SC3R was incredible, if inaudible, and the turn-in was so insanely quick, it felt like I was driving a completely different car. All the ingredients were there, but the lap times never materialized. The tires made the car feel like I had all the nannies on, and took the fun out of driving. In the end, I went a second faster on V730 than I did on SC3R. I recently traded them away for a used set of RT660s. I’ve also had the devil of a time getting my rebate, which is part of why I bought them in the first place. I’m done with Goodyear.

- Michelin Pilot Super Sport – These were the OE tire on the base Veloster N (non-Performance Pack), and came in a smaller 225/40-18 size on that version. I got them for free on Facebook Marketplace with half the tread remaining. They are easy to drive at the limit, but have an unusual sound, more of a protesting whine than a painful howl. The PSS are a generation older than most 300 TW tires, but were within a second of the V730 or SC3R. I corded the outside shoulder, just like every other tire. Man I need coilovers.

The following table is how I’d rank the tires on my Veloster N. I’ll probably get some disagreements here, but I like a playful tire that lets the car dance, and lap times matter don’t as much to me as having fun.

| Tire | Grip | Longevity | Price | Fun | Grade |

| SC3R | A+ | D | D- ($325) | D | C- |

| PZ4 | C | C | B ($175) | C | C+ |

| RT660 | A | C | C- ($250) | C | C+ |

| Crosswind | D | C | A+ ($65) | C | C+ |

| PSS | C | B | C+ ($175) | B | B- |

| VR1 | B | B | C ($230) | B+ | B |

| Blu Trac | D | A | B+ ($165) | A | B |

| V730 | A | B | B- ($200) | B- | B |

In the future I have two choices: get coilovers so that I can use better track tires, or switch to endurance tires with a symmetrical tread pattern. RS4s are the easy button, working well with camber challenged cars, and allowing me to flip them once, after I wear the outside shoulders.

The more expensive choice is to buy coilovers, which allow more camber and corner balance the car, and that would reorder my tire list completely. The negative camber would also allow the wheels to tuck under the fenders better. With that I might be able to fit 18×9 +45 wheels and 245 tires.

But… this is still a street car and I’ve ruined other cars in the past making them too track focused. I’ll revisit this conundrum in 2025.

Brakes

Muzafar Umarov manages the N Track and Autocross group on Facebook, and is a knowledgeable source on all things N. From him I learned that the Veloster N brake bias starts at roughly 70% front, but changes dynamically based on slip. Brake bias is controlled electronically for each wheel, and can shift to as much as 93% front if the rear wheels are locking.

This is both good news and bad news. If you’re accustomed to using the rear brakes to rotate the car on corner entry, you’ll be disappointed. The system essentially prevents corner entry oversteer, intentional or not. This infuriated my brother, who swore the traction control was on, even though it was turned off in the custom settings.

This also means that putting higher friction brake pads on the rear is a waste. Just as the dynamic brake bias system won’t help you turn the car on corner entry, it also won’t stop the car any faster. The sticky rear pads will just transfer more bias to the front brakes sooner. As a result, even the very serious folks at GenRacer are still using the OE rear brake pads.

And for that reason I’m also using OE rear pads, and will be for the foreseeable future. They are inexpensive, wear is imperceptible, and there’s no reason to use anything else. Life can be just that simple.

The OE front brake pads are reported to be quite good as well, and can do autocross and light track duty as long as you use the OE tires. But they are a little expensive, and the cheap hack is to use the Elantra N pads, and reuse the Veloster N shims.

But I don’t know about that, since once you upgrade the tires, you’re going to want better than OE pads. Knowing this, I switched the front brake pads to Porterfield R4-E immediately upon delivery.

This is a pad I have racing experience with, and as someone who’s never had antilock brakes on a track car before, I typically prefer pads with a lower friction coefficient. I believe the R4-E (E is for Endurance) come in around .46 mu, which is quite a bit lower than most serious race pads. As a result, they probably require more brake pressure. But I like the way they feel as I release the brake pedal, and that’s more important to me than initial bite or maximum stopping power.

Another reason to use a less aggressive pad is that several Veloster N owners have reported getting ice mode when using higher friction track pads. This can overwhelm the stock calipers and ABS system, and send the car into a panic. And so there are at least a few reasons for me to use the R4-E (the E is also for Economy).

The pads cost $210, which is $100 less than what you’d pay for most hybrid street/track pads, and half the cost of a dedicated track/race pad. I leave the R4-E on for daily driving, and they stop fine when cold and don’t squeal annoyingly like an aggressive track pad. (Although I understand some people like that.)

The way the R4-E work on both street and track remind me of the old Stoptech 301, before they switched manufacturing plants. That was a true dual duty pad, but it lasted about half as long as a R4-E. Still, they were less than half the price, and I used them without complaint for years.

Admittedly, I don’t experiment much with brakes, but Gregg Vandivert has done a ton of brake pad testing on his Elantra N. He had a problem using the Porterfield R4 (not R4-E) compound; the pads cracked and separated from the backing plates. The reason this happens is because Hyundai uses a cheap single piston caliper, and so the backing plate needs to be ultra stiff, or it flexes.

Gregg says Porterfield has two thicknesses of backing plates available, and you can special order pads with the thicker ones. Well, my R4-E pads have not cracked or separated, and so perhaps the E pads come with thicker backing plates to begin with? I will need to ask the folks at Porterfield at some point.

In any case, the brake pads are just fine for street and track driving, and they held up for over a year of both. Eventually the brakes started to fade on track, and I figured it was time to change them out. When I pulled them off I noticed they wore evenly inside and outside, and I had used 99% of the friction material without getting into the backing plates. I got lucky there.

Moving on from pads to rotors, I’m now just onto my second set. The service limit is 28mm and that’s where mine are at the outside edge, but down near the center they are 27.2mm.

It looks like I’ll need to replace rotors every two sets of pads, but if I get pad-curious then I’ll do both at the same time so they bed in properly. I paid $140 at Parts Geek for the front rotors, while my local Hyundai shop wanted $400 for essentially the same thing. Areyoufuckingkiddingme?

Two sets of front pads and one pair of rotors works out to $540, and that covers maybe two years. I don’t know how long the OE rear pads and rotors last, but certainly longer. That’s some serious economy, and it surprises me that Veloster brakes are as cheap as Miata brakes.

Fuel and engine modes

The Veloster manual says to use 91 octane, but I use 93 most of the time, because that’s what’s available. However, many of the pumps here only have non-ethanol 90 for Premium (lots of boats and such in this area). I don’t know what the power difference is between 90 non-ethanol, 91, and 93, but it may get more power out of 93 because of the higher octane. I don’t know if the VN has the “octane learning” feature of the EN, but I’m pretty sure the ECU will pull out timing when it senses lower octane. But then again, ethanol burns at 80k BTUs, while gasoline burns hotter with 118k BTUs, and so maybe I should be running non-ethanol?

I get exactly 7.0 mpg on track at Pineview and NYST. Every time. My friend Chris is only a couple tenths of a second slower than me on Pineview’s short track (45 second lap) and gets 2 mpg more than I do. So it’s interesting to see the diminishing returns on driving the car harder. At Watkins Glen I get a miserable 6.0 mpg. In practical terms, this means emptying a 5-gallon jug every track session.

On the highway I get mostly 32-33 mpg with the N wing, and I lose maybe 1 mpg with the ducktail spoiler. With a wing on the car, it gets just under 30 mpg, which is kind of surprising, because I thought that ducktail would have more drag. I haven’t done an accurate two-way test over a distance though.

The Veloster N has four different pre-set driving modes that change engine response, exhaust note, suspension stiffness, steering quickness, traction control, rev matching, and the electronic limited slip diff. I only use one of the pre-set modes, Normal. Economy mode doesn’t do shit, and the performance modes are a collection of settings I’d never use together.

Thankfully Hyundai made a N Custom mode that allows you to adjust each setting individually and save it as a custom setup. Mine has the suspension set to soft, and a quiet engine note with none of the pop and burble nonsense. I turn all of the nannies off, including rev matching, and max out the eLSD. I haven’t decided which of the three steering modes I like best, but I can change that on the fly using the touchscreen.

I use the Normal driving mode when I’m on the street, or when I am on track and it’s raining a shit storm. Compared to my N Custom mode, Normal is about a second faster in the wet and about 1.5 seconds slower in the dry. So I definitely appreciate having the options.

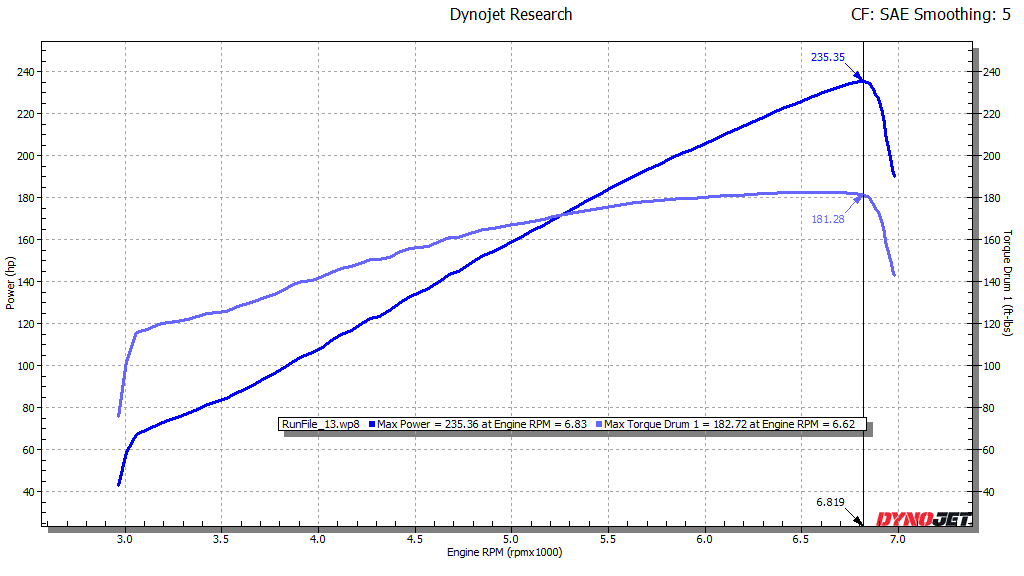

I dyno tested all the engine modes and they put out the same power. Eco mode is supposed to limit boost pressure, but it doesn’t make a difference on my car. I got 244 hp at the wheels on a Dynojet, and that’s 10 more than I expected.

Someone said the different engine modes don’t change power, they change how the engine responds. But given how the modes are identical on the dyno, I’m skeptical, I’ll A/B test engine response on track and see what the stopwatch says.

Finally, there was a recent software update that changes a bunch of things in the N Custom mode. I like the new layout, and appreciate that Hyundai is still making updates to a car they discontinued. I keep the updated software on a keychain USB drive in case I meet someone with a EN, KN, or VN that hasn’t made the update yet.

Track warranty

Arguably the best reason to buy a Hyundai is for the 10-year powertrain warranty. I bought mine as a Hyundai-certified pre-owned car, and so I’m covered until November 2032. I also upgraded to full bumper to bumper coverage, and so if anything goes wrong with my car in the next eight years, someone else is fixing it. And because this is a N car, the warranty extends to track use.

In fact, I’ve already used the warranty. The engine blew up on track at Waterford; Hyundai picked it up at the track, fixed it, and delivered it to me 500 miles away. They even paid for the rental car to get me home. I suspect in the next 8 years I will be using the warranty again.

Hatchback life

There aren’t a lot of sports cars that have enough room to transport a set of tires inside the car. Of course most 4-door sedans can do this, with two in the boot and two on the rear seats, but how many proper track cars can swallow a set of slicks? The Subaru-Toyota BRZ-86 was apparently designed to carry a set of track tires in the back, and I’ve seen four tires disappear inside a BMW 1-series. So I imagine that most BMW coupes can manage this as well.

Hatchbacks have the advantage here, and when you fold down the rear seats, even a diminutive MINI Cooper can carry four tires inside. But can you name any track car that can transport eight tires inside? With the space-saving Modern Spare in the well and one on the front seat, that’s actually nine!

The first time I went down to the A2 wind tunnel, I transported three splitters, five wings, two spoilers, a diffuser, boxes of tools, spares, and other parts inside the car and drove the 10 hours to Moorseville. Try that in any other car you’d actually take to a wind tunnel.

And if this wasn’t enough space already, I added a trailer hitch so that I can use a cargo tray or small trailer. The Veloster trailer hitch was designed for the base model Veloster, and required some modifications to fit my car.

Aerodynamics

My Veloster has been to the A2 wind tunnel twice, and now I know more about hatchback aerodynamics than I ever dreamed I would. The OE body has a drag of .416 and makes a tiny bit of downforce, which is pretty surprising, since most cars make lift.

Front downforce was easy to get, and even a flat splitter made 135 lbs of downforce at 100 mph. My curved splitter made 195 lbs, and coupled with upper and lower canards and hood vents, total front downforce was north of 300 lbs. And this is without cutting vents into the fenders or extracting air behind the wheels, which you would do on a proper race car, but I may never get around to on a daily.

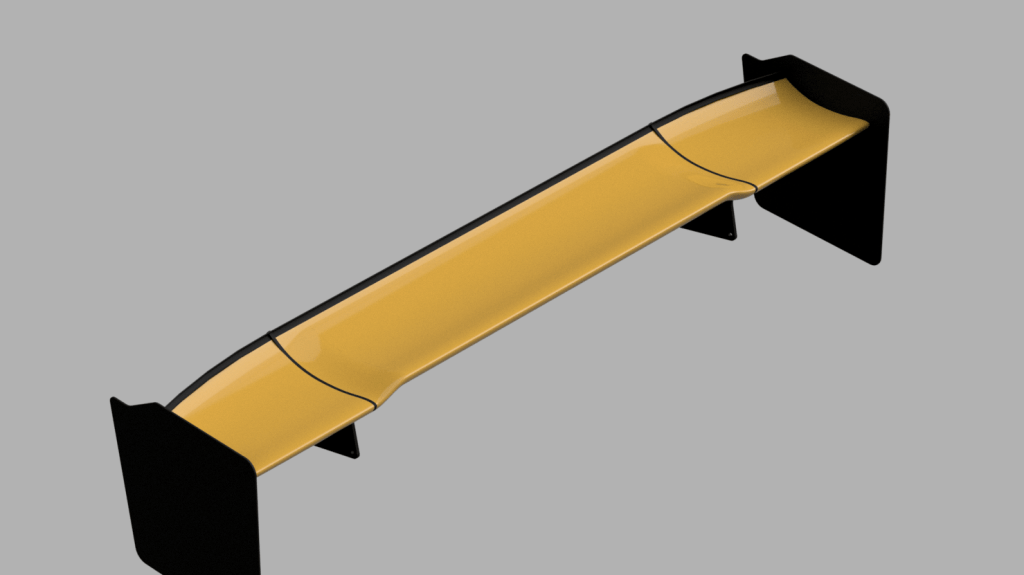

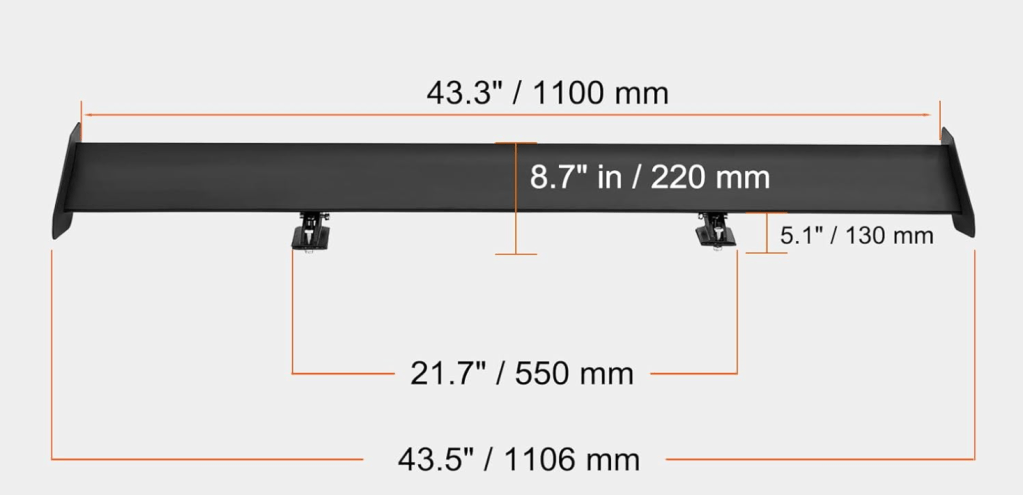

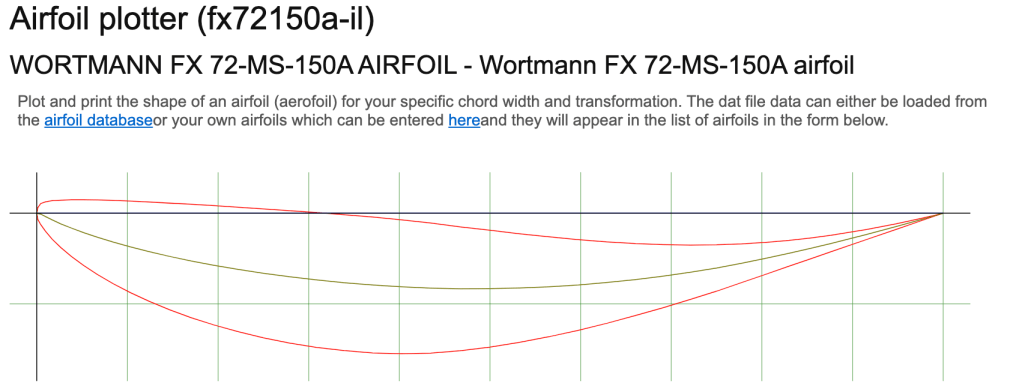

At the other end of the car, wings didn’t perform as well as I expected, and even the Kamm-back shape is a compromise over a proper coupe or fastback. As such, most wings up to 55” span had lift-to-drag ratios less than 4:1. A 70” Wing Logic gave the best results at 7:1, which is more a function of the wingspan than the shape of the wing; it’s obviously important to get the ends of the wing into clean air where they can get away from the hatchback roofline.

If wings were disappointing, spoilers were a revelation, as they made both front and rear downforce. (Wings reduce front downforce through leverage; Spoilers aggregate pressure over the l roofline, and some of that is in front of the rear wheels.) Spoilers can’t get as much total downforce as a wing, but they work surprisingly well if you’re not going to add a splitter.

The biggest surprise was that adding a 1” Gurney flap on the OE N spoiler gave a better L/D ratio than all but the largest wing.

At 100 mph, the OE wing makes 30.8 lbs of downforce and loses 2.5 hp due to drag. With the wicker-kicker it makes an astonishing 123.6 lbs of downforce and uses 8.3 hp. (These numbers are compared to the base model, which has a roof extension, but no wing).

The Gurney flap information isn’t (yet) in my wind tunnel report, but there’s over 50 pages specific to the Veloster N, going nose to tail on aerodynamic parts, simulated lap times, and a lot of discussion.

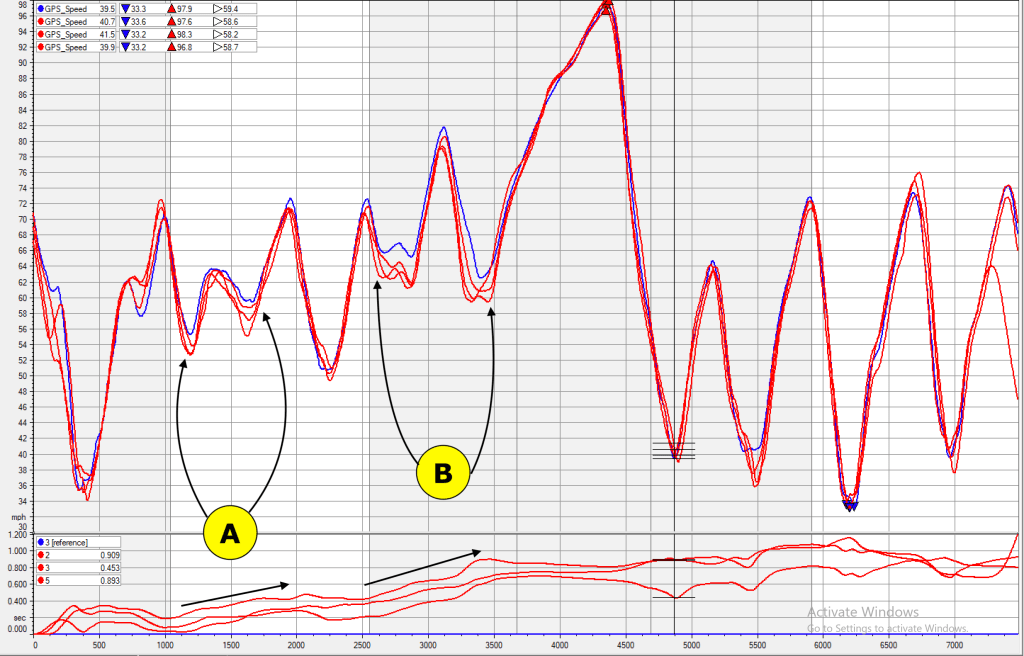

I also did some practical testing of wings and spoilers at Pineview Run and NYST. The short story is that my Veloster went 2.5 seconds faster with rear downforce alone. Given that, I wouldn’t even bother adding front downforce unless you have a really significant wing to balance it out.

Conclusion

In the past year and a half I’ve done probably 30 track days in my Veloster N; I’m still smiling. It’s got enough cargo capacity for everything I bring to the track, and a comfortable ride that makes long-distance track treks a pleasure. It has adequate power, and handles better than it should. Even on track like Pineview, which has a lot of long corners and uphill switchbacks that punish FWD cars, it’s fast and fun to drive.

As track cars go, it’s economical. It doesn’t need expensive brake pads or ultra grippy tires, and seems to work just as well with mid-performance items. If you want to keep the warranty, you can’t modify engine parts or tuning, which leaves very little to spend money on. Except gas, as it is pretty thirsty.

The funny thing is, I’m actually looking forward to when the car is out of warranty, and I can install a bigger turbo. With a larger turbo, all the bolt ons, and a ECU tune, it might get down to a 10:1 lbs/hp ratio. Then I’ll gut it, cage it, and race whatever dumb series will have me. But I’ve got 8 years of wringing the snot out the stock engine, and I’m not at all disappointed with that.

I daresay I’m forming an emotional attachment to this car! It’s the amalgamation of so many cars I wanted and never bought: It’s the Honda CRX I pined for in college, but modernized and powerful; It’s the later CR-Z with double the power and nearly the economy; It’s the 3-door cousin of a MINI Clubman JCW, but with better aerodynamics; It’s as weird as the M Coupe “clown shoe” I nearly bought, but easier to live with.

And it’s so much fun! I love tossing the car into an early apex, forcing it into a four-wheel drift, and then digging it out with the front wheels. It’s Miata like, in its combination of economy and ability to bruise egos everywhere it goes. If you have a BMW M car, Corvette, or Porsche, you’d better be a decent driver, because the hurt machine is coming though!

This is probably the last car I buy that isn’t an electric self-driving killjoy mistake, and so I’m going to continue to modify it for more fun. I’ve already removed the rear seats and put in a flat cargo floor. Next I’ll install a harness bar and race seat. Sometime this winter I’ll figure out a DRS dual wing, because hitting a button on the straights is a plus one to fun. And maybe I’ll hook that up to an adjustable splitter as well. Let’s see what happens in 2025.