This winter I went to Florida to visit my in-laws for a couple weeks. My original plan was to drive my Veloster down and do some track days. I’d take a break from pickleball and cribbage, and do some driving at a couple tracks I’ve been to before, The FIRM and Sebring. And then maybe pick up a new track sticker after hitting Homestead.

But The FIRM didn’t have any open track days for the two weeks I’d be down south. Same deal with Homestead. There was only one open event at Sebring, but it was a Track Night in America, and I swore I’d never do one of those again. The one TNIA I did at Palmer felt like UDWFCNIA (Unskilled Drivers in the Wrong Fucking Class Night in America).

So with no public track days on the calendar, the only chance I’d have to drive on track would be a private race track. As luck would have it, Circuit Florida is near my in-laws.

If you haven’t heard of Circuit Florida, it’s because it’s a members-only track, similar in concept to Monticello, M1 Concourse, Apex Motor Club, Atlanta Motorsports Park, etc. These are exclusive country clubs with initiation fees that range from $15k to $115k, and you pay annual dues on top of that. Many of these tracks have onsite garages and/or condos, and some require that you buy property to get into the club.

As expensive as they are, this business model seems to be gaining in popularity, and more private tracks are popping up. From a historical standpoint, it’s not surprising. Horses were once used for transportation, but are now mostly a pastime for the wealthy. In the future, that’s the way it may go with cars; most of us will be transported by electric self-driving shitboxes, while rich people will keep a stable of cars, and use them for recreational track driving.

Whatever happens in the distant future, the immediate future required a call to Circuit Florida to make an appointment. The track manager, Adam Ricardel said I could take some laps in my Veloster. But in the end I decided not to put 2400 miles on my car for a few parade laps. Instead we took my wife’s Mini Cooper to Florida, which is on excellent snow tires, and that would turn out to be important an important decision for the return trip.

Circuit Florida is awesome

Circuit Florida is the brainchild of Paul Scarpello, a successful businessman who had the means to buy the land and build the track by his lonesome. As such, the entire operation isn’t a fantasy-land held up in committee, but a real-world commitment driven by a single vision. That vision includes hiring Bob Barnard to design the layout, acquiring the most expensive motorsports-grade asphalt available, doing a tits job of paving it, building upscale condos and garages, and executing all of it with pace and precision.

Paul’s track manager is Adam Ricardel, who has a long list of credentials (Chief Instructor this, blah blah blah that), but I’ll tell you the one thing you need to know about the quality of his character: he races an E30 in Champcar (I’m pretty sure I’ve raced against him at Sebring and possibly WGI). He’s a savage wheelman who can can talk at eye level with both millionaires and average Joes, and is exactly the guy you’d want to be in charge of the track.

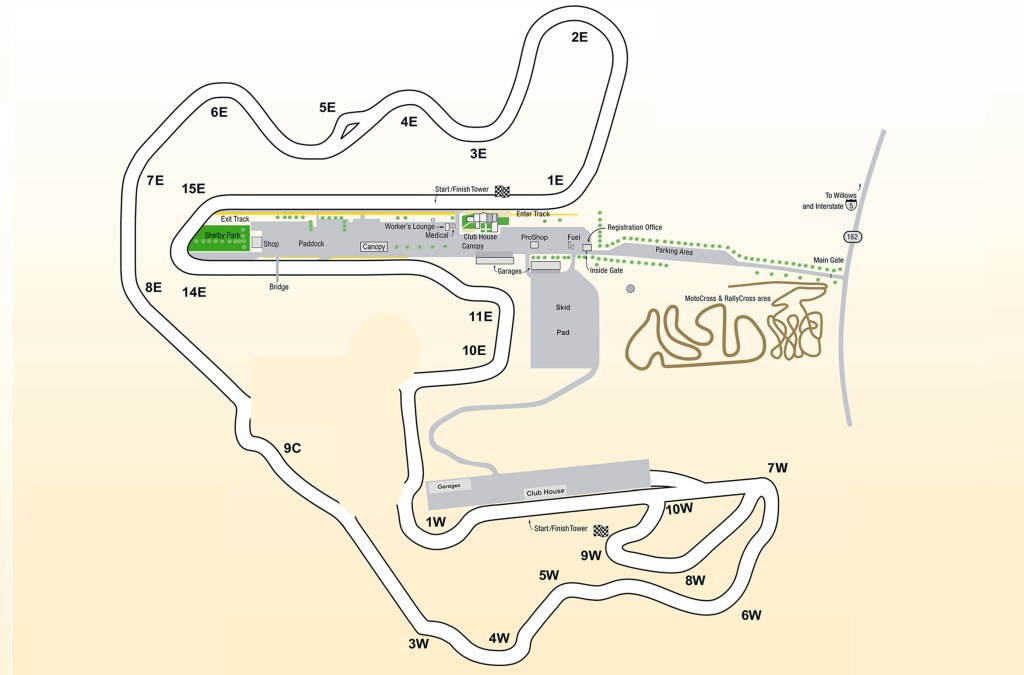

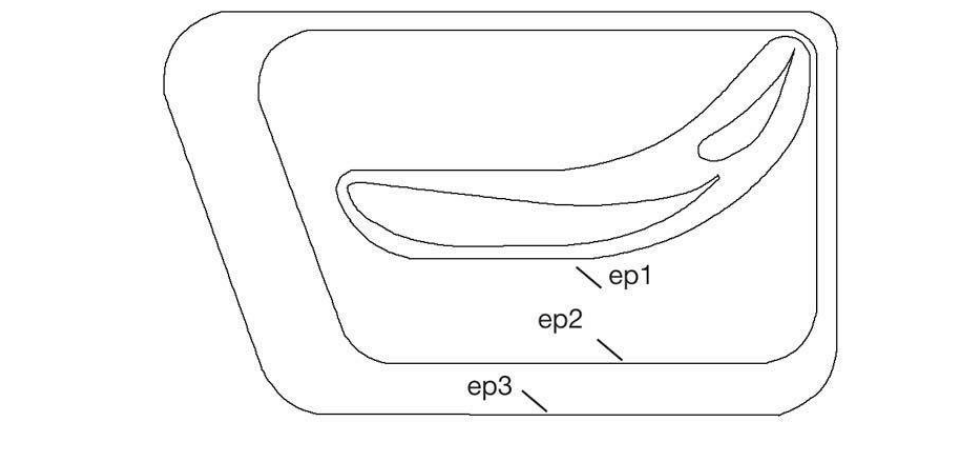

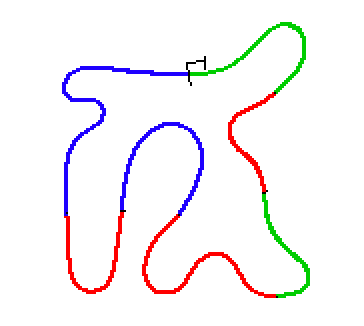

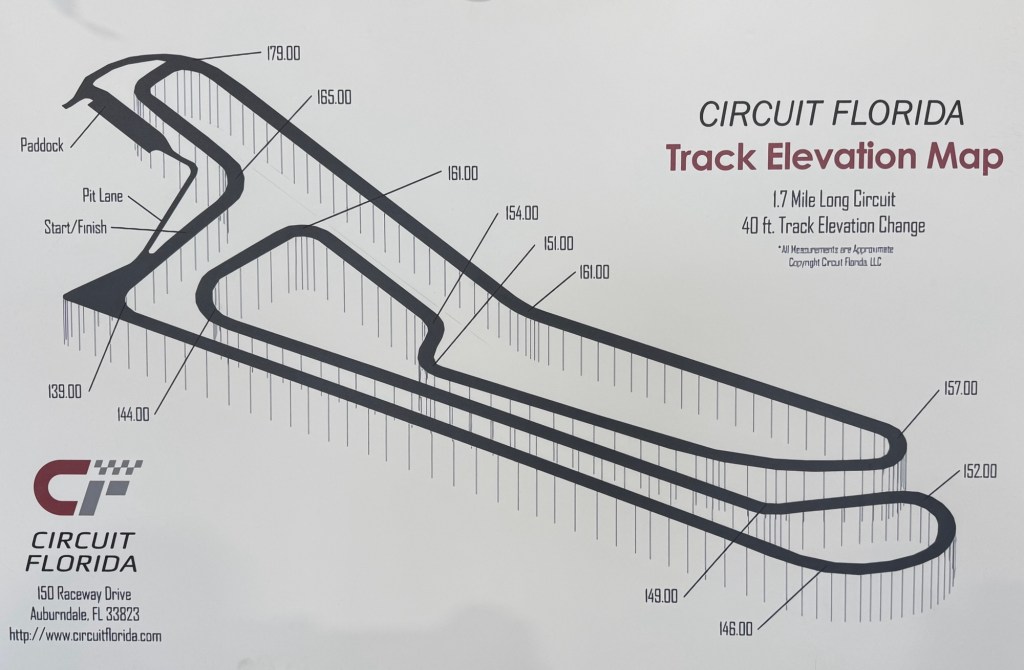

Circuit Florida has a paperclip layout, optimized for the available space, with 1.7 miles fit into fast straights and technical corners. Adam drove me around in one of the track’s fleet, a Mustang something or other, and while the car was forgettable, the track was not. It’s goddamn fantastic.

Being situated in Florida, you’d be right for thinking it’s flat. But then you’d be wrong. There is a surpising amount of elevation on this track, and it’s used strategically to create a more technical layout. With long straights and slower corners, both supercars and Miatas would be at home on this track, but the latter would be more fun. In fact the club is buying a fleet of MX-5 Cup cars just for members to race around in.

Of course there will be a swank clubhouse, and they are building a gym and restaurant, and maybe a business center, I forget. That kind of thing doesn’t blow my skirt up, but the track has my utilikilt up around my shoulders. And here’s the kicker, Circuit Florida recently received zoning and site plan approval for an extension of its racetrack to 2.4 miles, a skid pad, off-road driving course, a 6-acre industrial pad site, and 75 additional trackside condos. Hallelujah.

So what’s all this going to cost? About $20k for a one-year trial membership. If you’re all-in from the get-go, the initiation fee and monthly dues also works out to around $20k per year for 10 years of membership. This is a rich person’s playground, and my Veloster would look a little out of place next to the member cars I saw lapping on track. There was a brand new 911, a Lamborghini LP610, a brace of McLaren 720S (one with an extra 150 hp), and a AMG GT with all the options. I’d have passed every one of them, but there’s always an inverse relationship to money spent and skill, especially with these kinds of clubs.

Frankly, these are not my people, and it feels weird rubbing shoulders with people that don’t have dandruff on them. But if I lived in Florida, I’d join this club for the same reason I pay for YouTube Premium: I hate commercials. But in this case it’s not so much commercials, it’s the morning drivers’ meetings.

8 am drivers’ meetings are a vampire draining 30 minutes of life from 100 people at a time. It’s the same shit every time: thanking the registrar and other clerks for doing their jobs, going over the flags we’ve seen before, how to do a point-by, basic safety rules, dumb jokes, and all the other shit we’ve heard over and over again. The unfortunate part is, if there’s truly anything important to be said, it’s lost in the chaff of sameness. There ought to be a TSA-Pre version of drivers’ meetings where we get a 3×5 index card with any important safety issues. And nothing else.

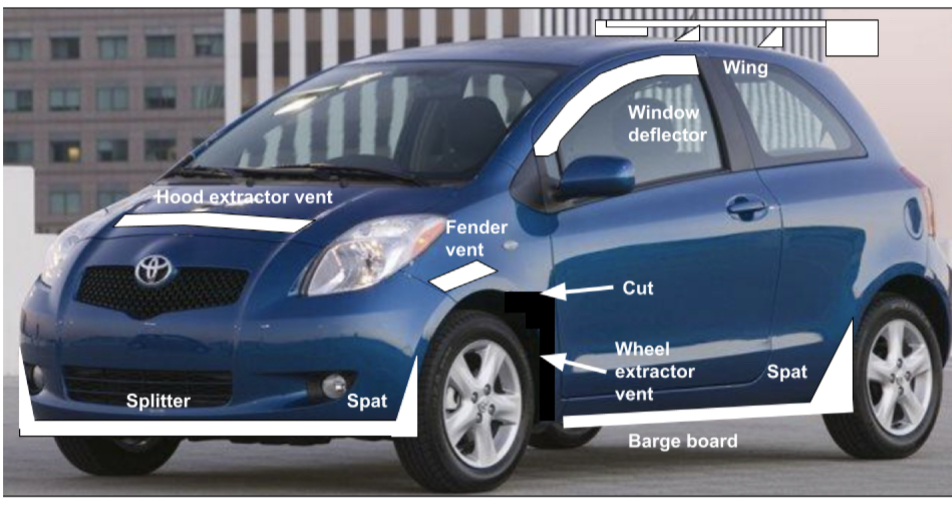

Rant off. The other reason I’d join Circuit Florida is the convenience. I like to be able to show up whenever I want, run some laps, and go home after a couple-three sessions. I also do a lot of aero and tire testing, and I need a fairly open track and the ability to pit and change things every few laps. I get that now at Pineview, and I require more of the same.

I’ve been a member at Pineview Run since 2019, and the experience has spoiled me rotten. Even if Pineview Run is rather small, being able to drive at a moment’s notice outweighs the combination of cost and butting heads with management. So, yeah, I’d pay a ridiculous amount to belong to a private track club in Florida.

And it’s honestly not that ridiculous. If you consider the average track day is $400, I’d break even after 50 events. I mean, if I was living in Florida, what else am I going to do with my time? I would 100% join Circuit Florida.

Florida Man

Florida Man is an Internet meme first popularized in 2013,[1] referring to an alleged prevalence of people performing irrational or maniacal actions in the U.S. state of Florida. Internet users typically submit links to news stories and articles about unusual or strange crimes and other events occurring in Florida, with stories’ headlines often beginning with “Florida Man …” followed by the main event of the story. – Wikipedia

I’ve laughed at my share of Florida Man memes, and it makes me wonder how many are actually true. Well here’s one that’s real:

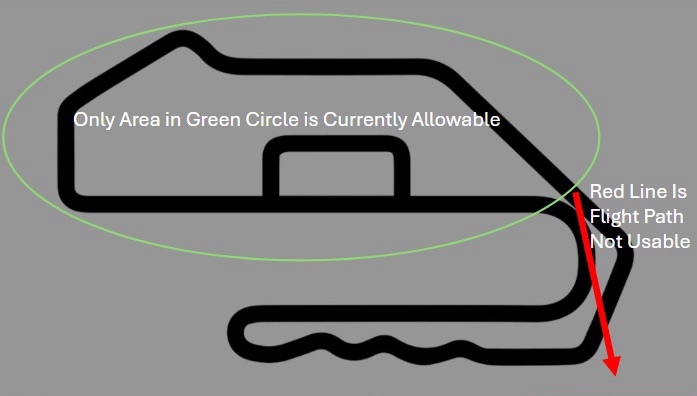

“Florida Man discovers that a small corner of a race track is within the restricted flight path of a neighboring airport and closes the track, incurring the wrath of local car racers, and nullifying years of track data.”

As the story goes, some Florida Man made an airport surveying error back in 1999, and when The FIRM took over the lease in 2013, they had no idea said map was off by a few feet. But Florida Man 2025 decided that this is an important piece of real estate for a flight path, and shut that part of the track down.

I have to think that if it was me that noticed this tiny discrepancy, I would have let it go; it obviously hasn’t been an issue in a quarter century of takeoffs and landings. But Florida Man got a bug up his fuselage about it, involved the FAA, and now The FIRM is embroiled in a legal battle with a Government agency. I can’t imagine how much fun that’s going to be. Thank you Florida Man, I’ve got a dick punch and a hertz donut for you.

The FIRM

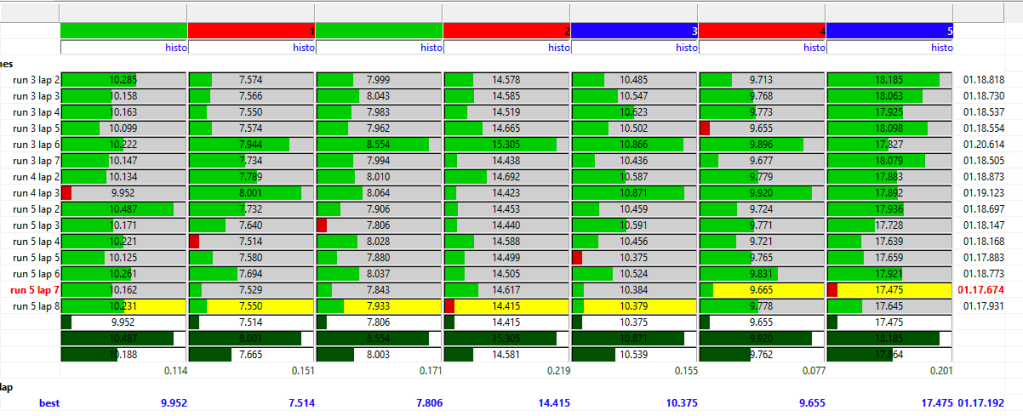

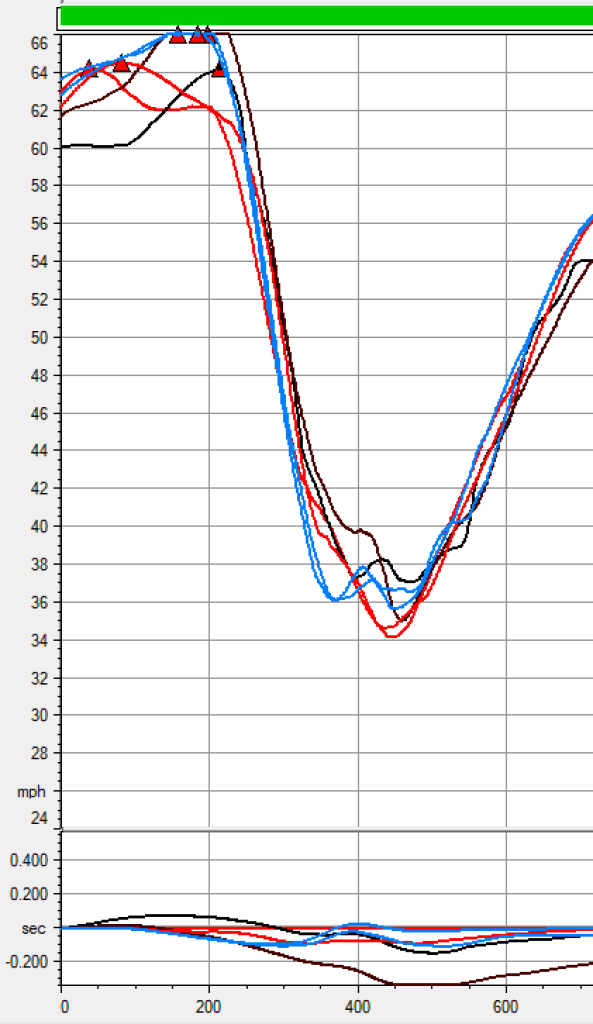

I only have one day of driving at The FIRM, in my buddy Brad Alderman’s ND2 Miata. The track is short and mostly flat, but it’s a fun combination of technical corners, one high speed pucker, and the biggest wall of Armco you’ve ever seen. Compared to places like Watkins Glen or Lime Rock, The FIRM is insignificant. Except for one thing: the Grassroots Motorsports leaderboard.

If you want to research car performance, a lot of people’s first stop would be the lap times from the Nurburgring. On this side of the pond we have don’t have the same kind of proving ground, but some journalists get together every year for Car and Driver’s Lightning Lap, which is a measure of something (if not an entirely accurate one). And then you have smaller and more accurate leaderboards, like the one GRM keeps at the FIRM.

If you check out Grassroots Motorsports ultimate guide to track car lap times, you’ll see a very good example of how to keep an accurate leaderboard. They list the tires, weather, and try to use the same driver as much as possible. If you click on the car, you’ll see an in-depth article, or even a video with data analysis. Unfortunately, whatever The FIRM does next, GRM is going to lose the ability to test new cars and compare that directly with the historical data that they’ve done such a great job acquiring.

Maybe there’s an upside to all of this, though. When The FIRM redesigns the track, perhaps they’ll be able to make some improvements. The big Armco wall is a tad intimidating, and the esses are so mild people just drive a straight line through them. So let’s be optimistic about the change, and maybe someone can figure out a correction factor to equate the old times with new.

In the meantime, did you know that the lap times from Toronto Motorsports Park are pretty close the The FIRM? Yeah, check out Speed Academy’s leaderboard and it’s nearly the same times. Let’s just cross our fingers that they don’t have a Canada Man.